Mongol Nomad Migration and its associated practices

Mongol Nomad Migration and its associated practices

Inventory

“Mongol nomad migration and its associated practices” included in the “National Representative list of the intangible cultural heritage of Mongolia”:

- “By the 92nd Order of the Minister of Education, Culture and Science on March 5th of 2010

- and updated by 84th Order of the Minister of Education, Culture and Science on March 16th of 2011

- and by 41st Order of Minister of Culture, Sports and Tourism on February 8th of 2013,

- and lastly updated by 759th Order of the Minister of Education, Culture, Science and Sports of Mongolia on November 29th of 2019.

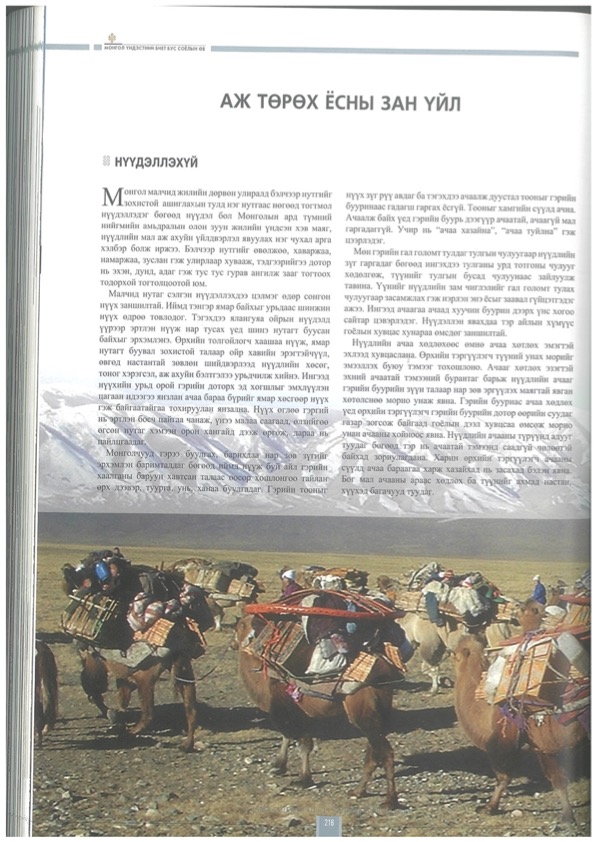

ICH Element’s Description

Mongolia is one of the cradles where humans have lived for long and nomadic herders managed to live in harsh climates for four seasons of the year and continue practicing pastoralism. The Mongolian nomadic culture was formed in the inseparable ties and cult of "Pasture - Livestock - Herdsman". In order to fatten their livestock and maximize their benefits those herdsmen migrate year-round to select pastures rich in nutrients, which is the basis for the formation and development of the nomadic culture. Herdsmen chose their winter, spring, summer, and autumn pastures in combination with the characteristics of the four seasons and created a unique distribution of grazing land.

It has been passed down through the generations as a wonderful method of regenerating the earth through nature. Herders do not migrate to the same place for a long time. They migrate in the direction where their livestock wants to go, and their livestock is in a perpetual cycle of well-being, breeding, and the ability of their owners to live without scarcity and to use their pastures properly. The migration tradition of Mongolia has led to the development of a rich heritage of intangible cultural heritage, with the content and philosophy of respecting nature, the living space, and other people. The main reason for frequent land changes is that it quickly creates the capacity for pasture and provides a chance for regeneration. The pastures are divided according to the season—summer, spring/fall, and winter based on the amount of grass and when the grass is sufficient to eat, which is often determined by geography, climate conditions, and season.

Simply put, herders stay in a pasture as long as there is enough grass. The spring (khavarjaa) and autumn (namarjaa) encampments are typically the most temporary. Summer encampments (zuslan) will usually have semi-permanent structures, such as milking pens and hitching posts. The winter encampment (uvuljuu) is always the most established, with shelters for animals, storage huts, and corals. Often in the summer, herders leave many possessions behind, because they travel in a smaller and lighter ger, with as little furniture as possible. Otor is a short-term seasonal migration, which is conducted mostly from the tail of autumn till the head of spring looking for greener pastures for their livestock. This is when (typically due to overgrazing or lack of rain), pasture is scarce and one or two members of the family will travel longer distances with their livestock searching for better pasture. The spring migration can be the toughest as the animals will be thin.

Since there are so many families living in the Otor pasture region during the winter and spring, no family stays in their pasture very long. Consequently, migrates frequently. The main reason for frequent land changes is that it quickly creates the capacity for pasture and provides a chance for regeneration. The rituals and customs associated with nomadic migration are slightly different from one another because of the difference in ethnic groups and the terrain's characteristics, in addition to the days of migration, the animals, and the equipment used to carry the load.

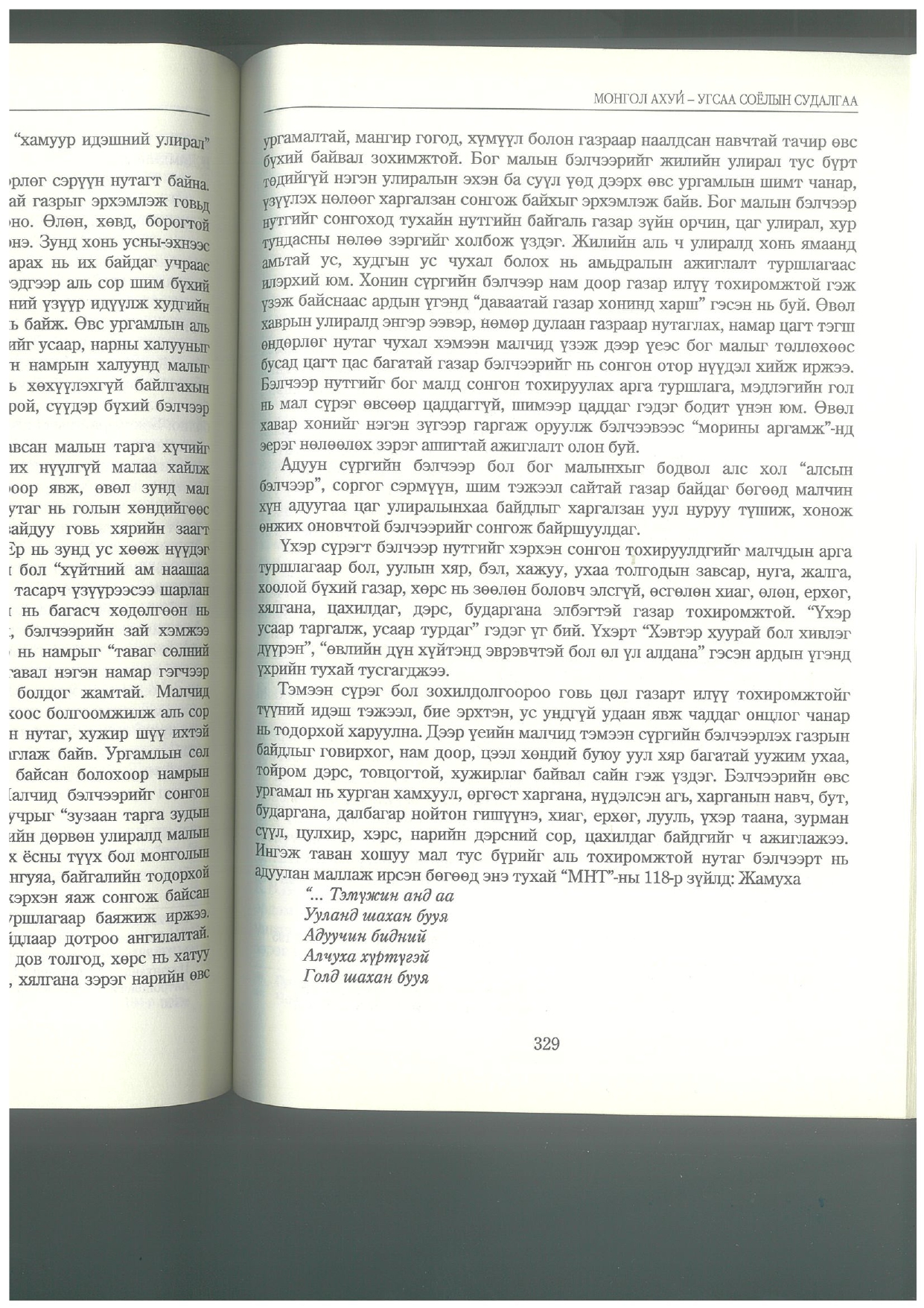

Distribution of ICH Elements

- 246.2 thousand herding households living in the Gobi, Khangai, high mountains, steppes and taiga regions of Mongolia.

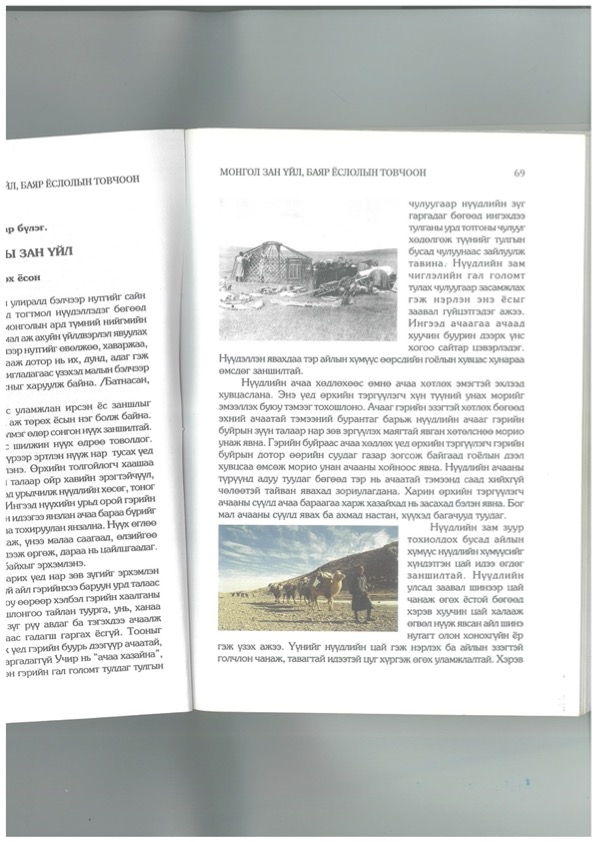

Types of Migration

There are many types by load, such as camel ridges, yak ridges, reindeer ridges, bullock-cart, and camel-cart. In the hot and dry climate of the Gobi region, herders live mainly by herding camels; these camels are trained from being young and used for carrying loads. Families who migrate by camel usually travel at least 50 kilometers to change their camels, and sometimes make long-distance migrations that can take up to five days. Herdsmen living in the steppe region use yak carts.

However, in rugged and high mountain areas, herdsmen cannot use carts, so they move on the ridges of camels and cattle. The customs of migration are directly related to the ecological features of the region. The herdsmen of the Khangai region move closer to the river during in the summer, while the Mongolian ethnic groups such as the Torgud, Uriankhai, Zahchin, and Durvvd of the Altai region follow their highland mountain migrations in the summer and in the winter at the foothills.

Significance of ICH element

The migration tradition of Mongolia has led to the development of a rich heritage of intangible cultural heritage, with the content and philosophy of respecting nature, the living space, and other people. Since there are so many families living in the Otor pasture region during the winter and spring, no family stays in their pastures for very long. Consequently, migrates frequently. The main reason for frequent land changes is that it quickly creates the capacity for pasture and provides a chance for regeneration.

Taking the number of livestock, cultural-ecological space, and geography of herdsmen's migration into account, migration types are identified as follows taiga area, highland area, steppe area, and in Gobi area. Mongolian nomadic customs and practices affect human morals and upbringing such as living in harmony with Mother nature, valuing and cherishing the water that washes the fallen land, lovingly protecting livestock pastures, flora and fauna and continuing the history of our ancestors, so it is a fundamental value for humanity.

The features and advantages of nomadic civilization can be considered as a whole system of creative activities and culture of nomadic people, which is developed based on the environment, pastoral activities, eco-friendly, wonderfully adapted, using their benefits and resources in accordance with their needs.

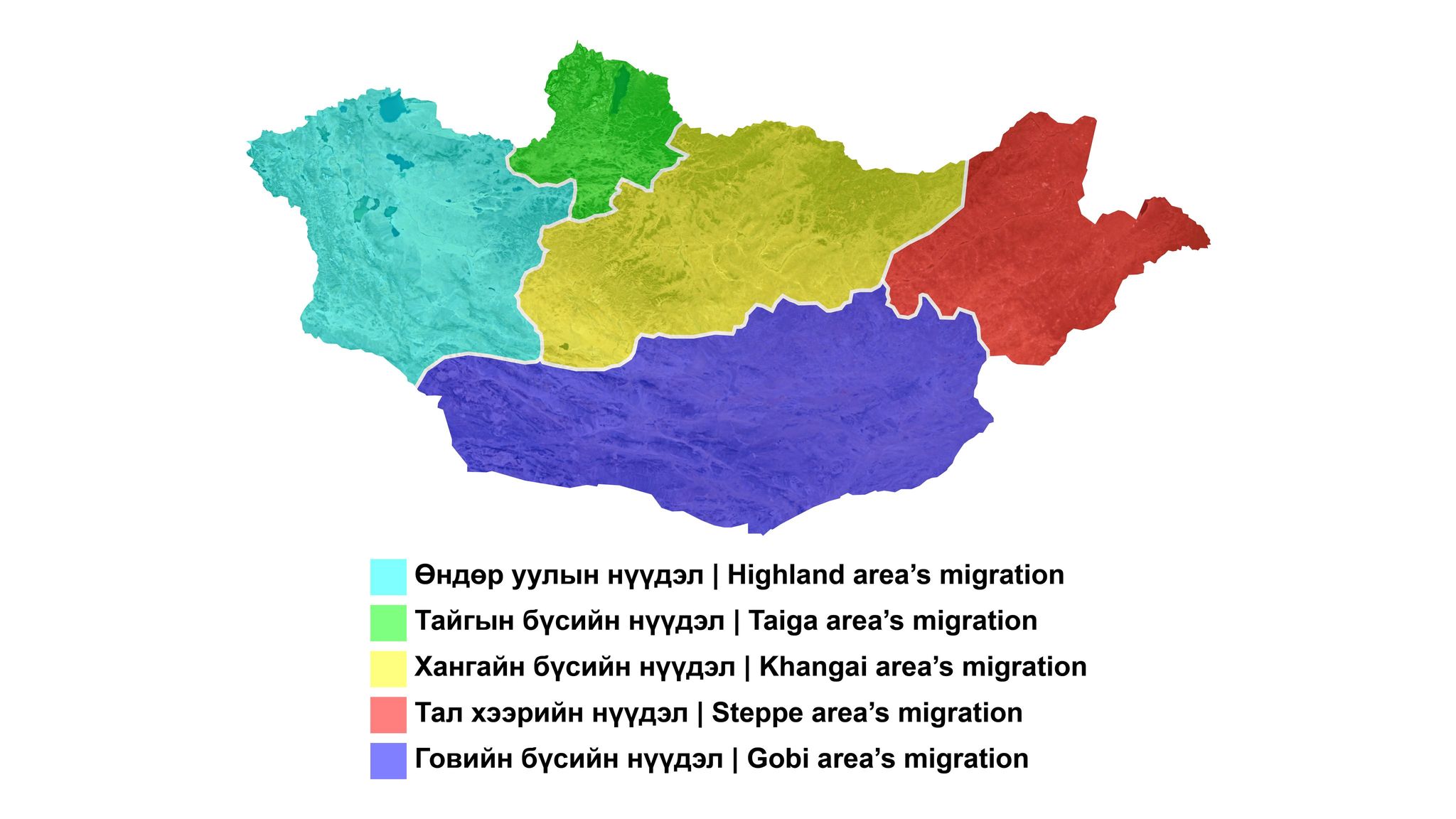

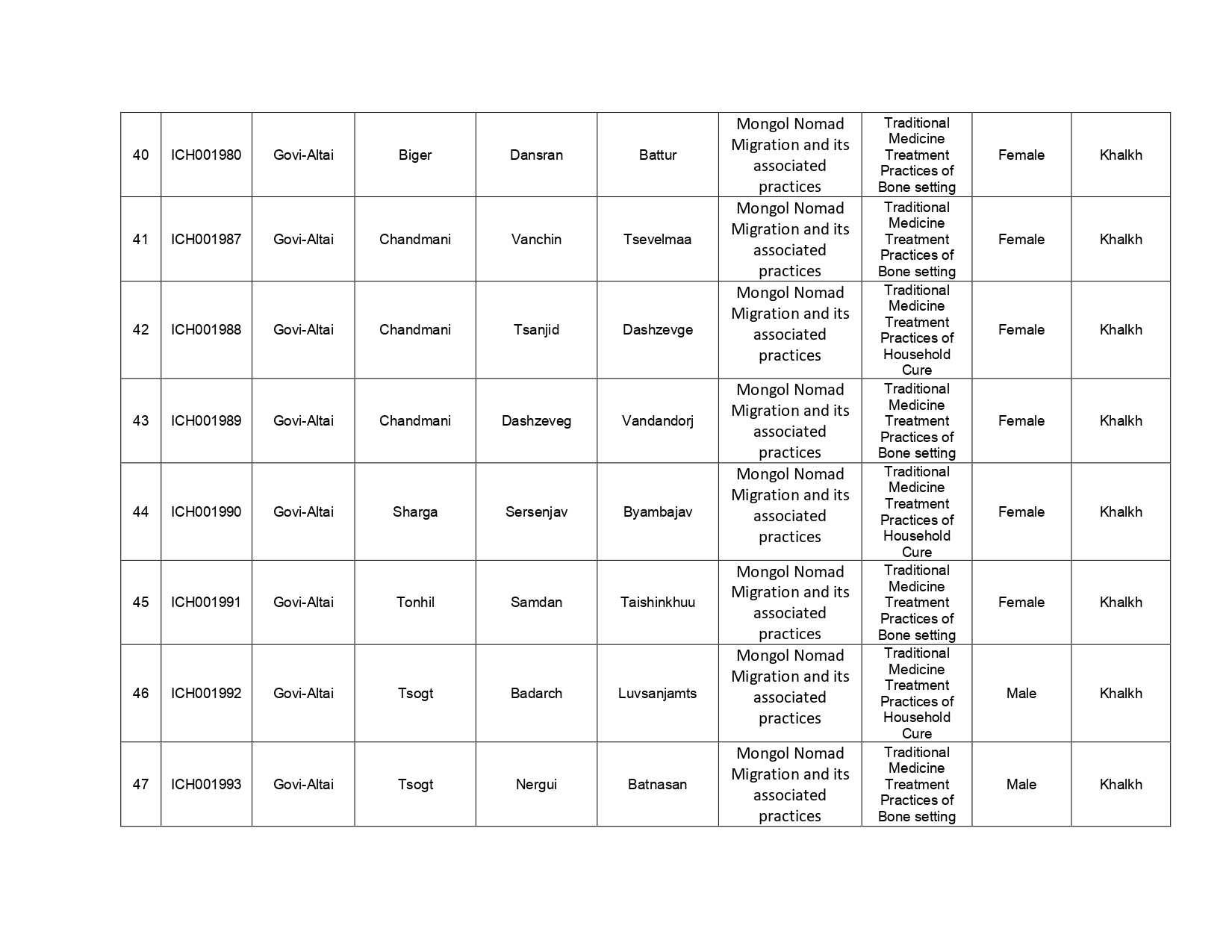

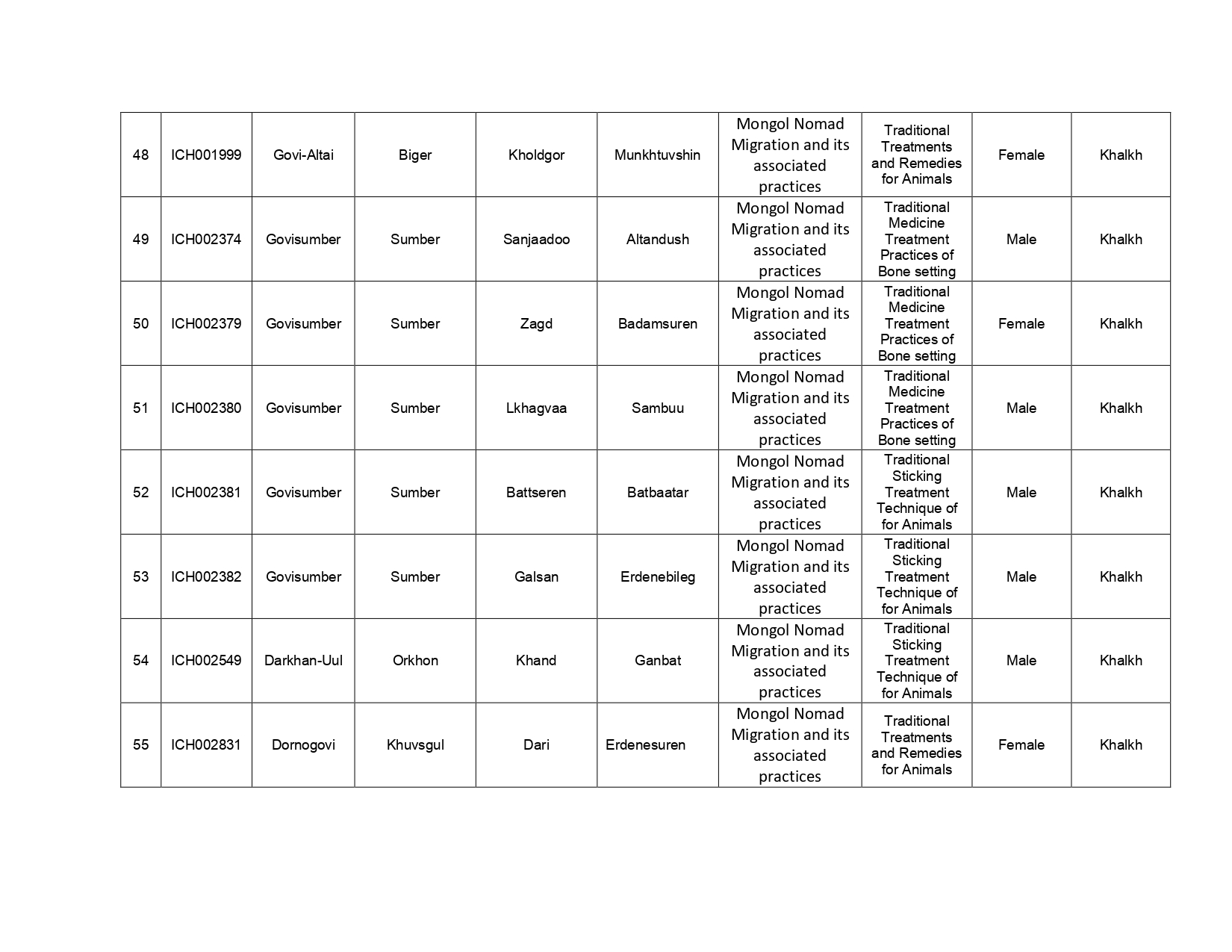

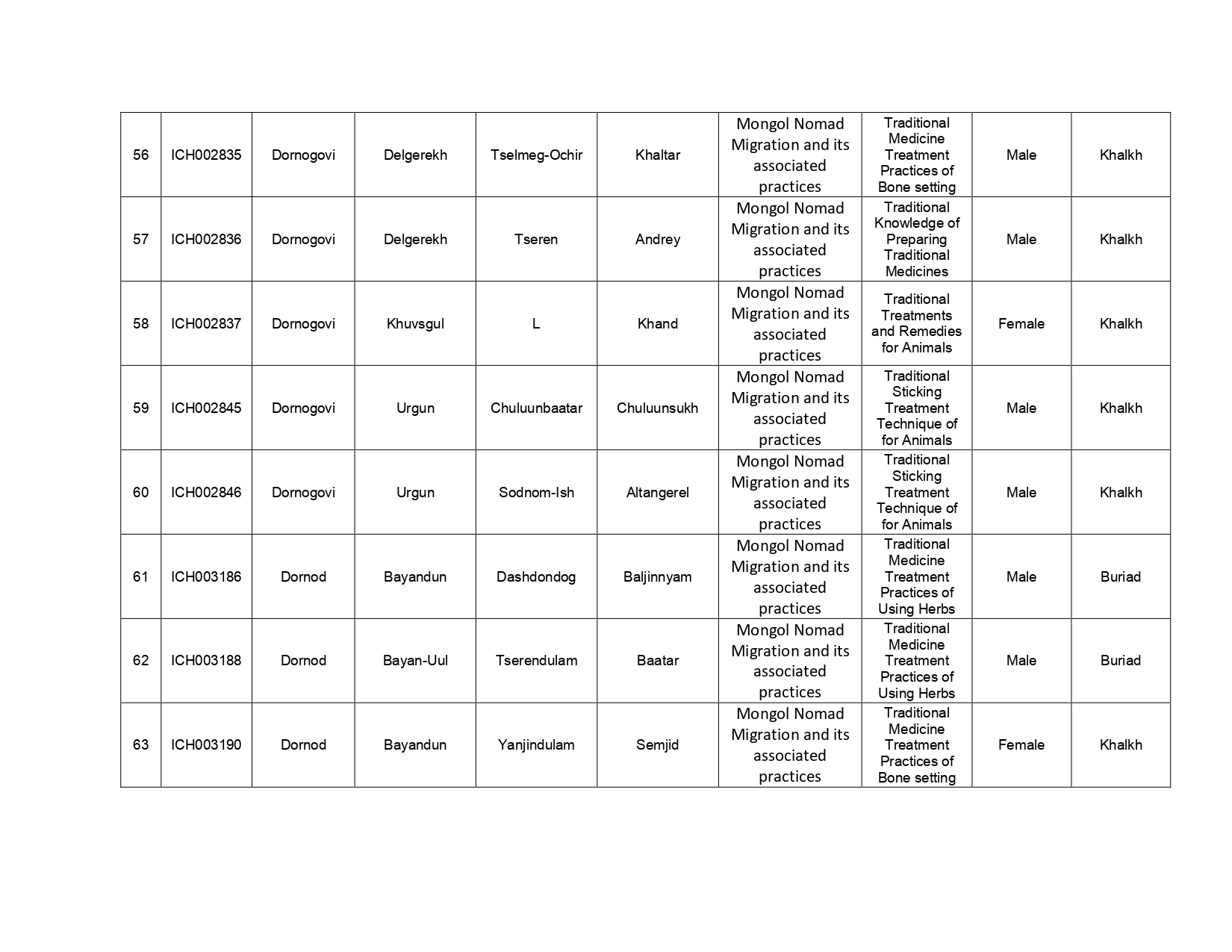

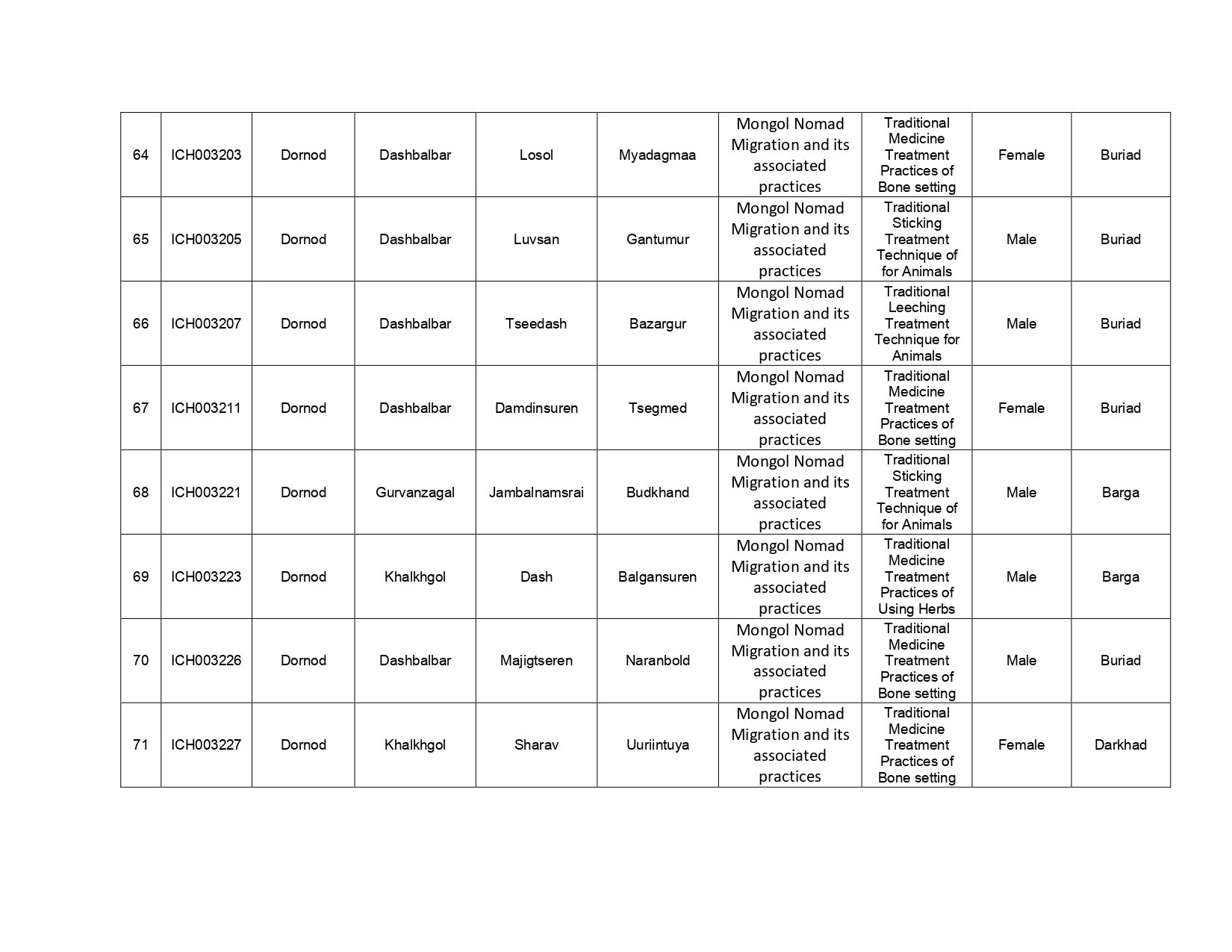

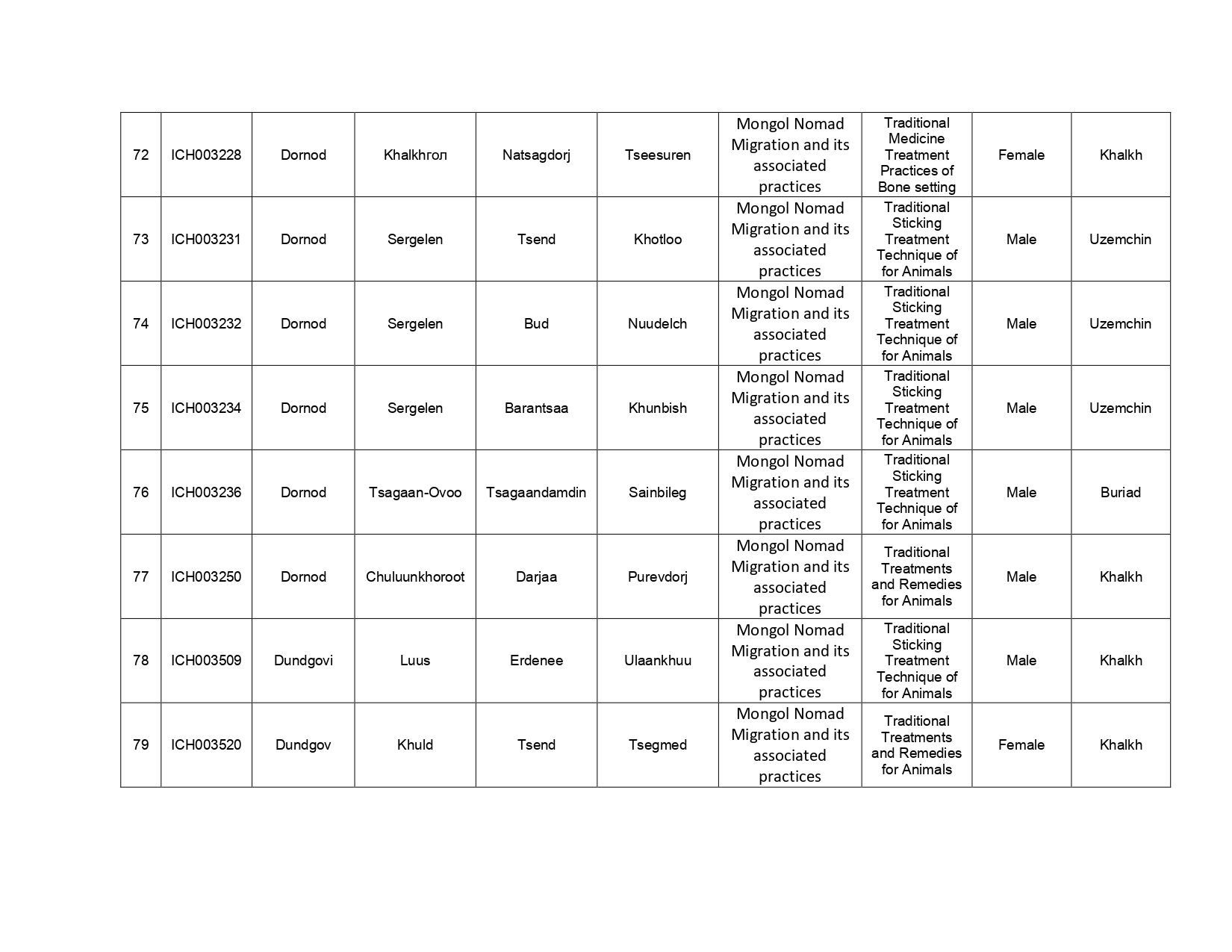

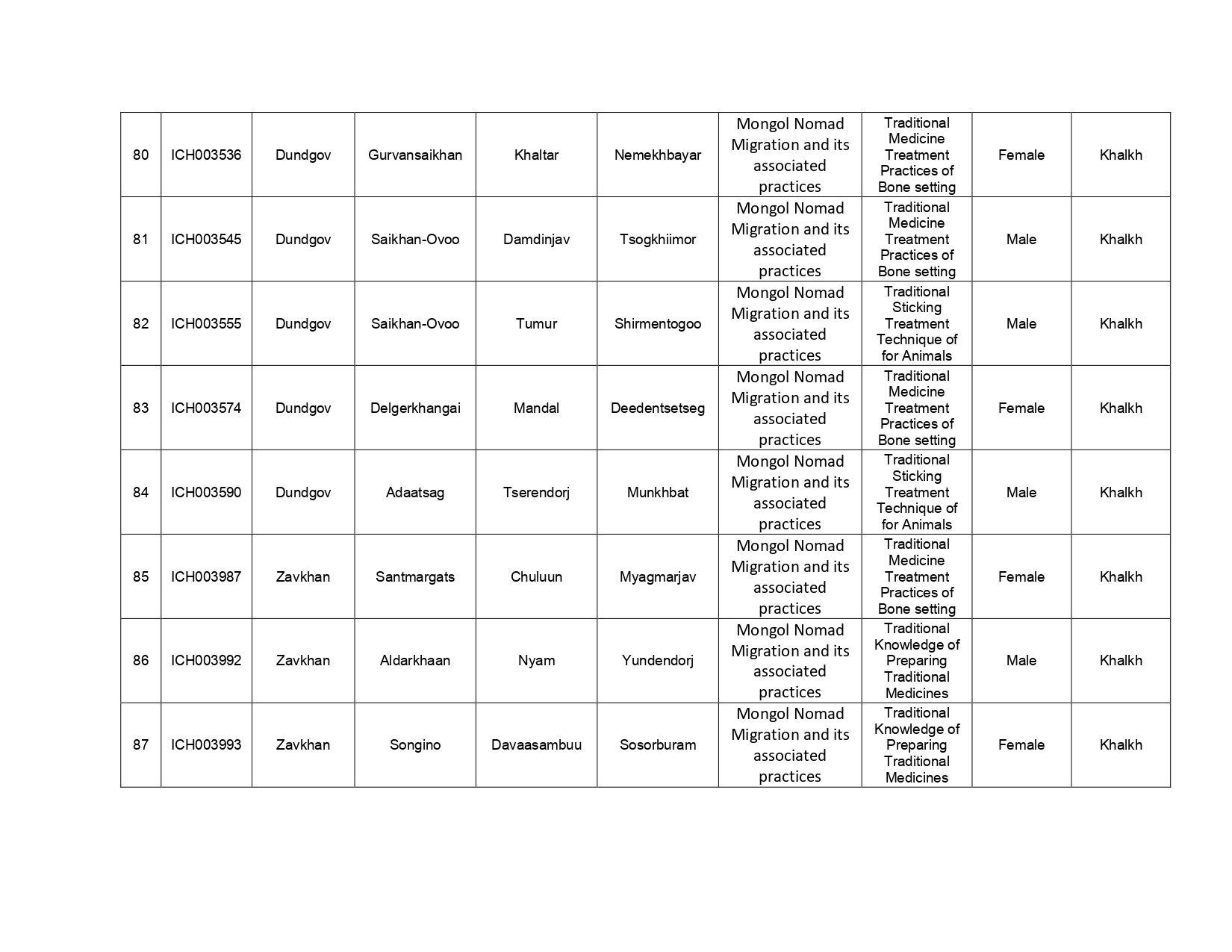

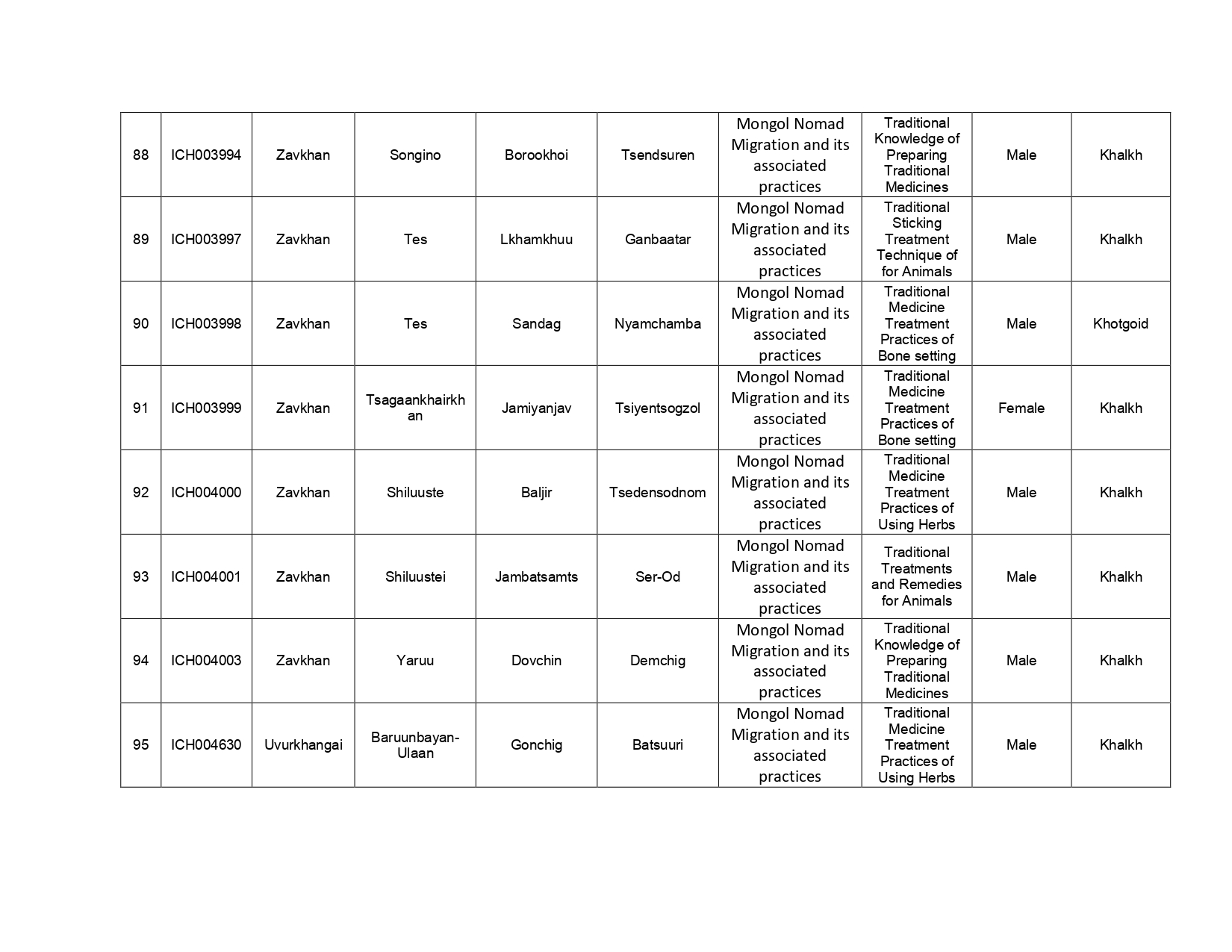

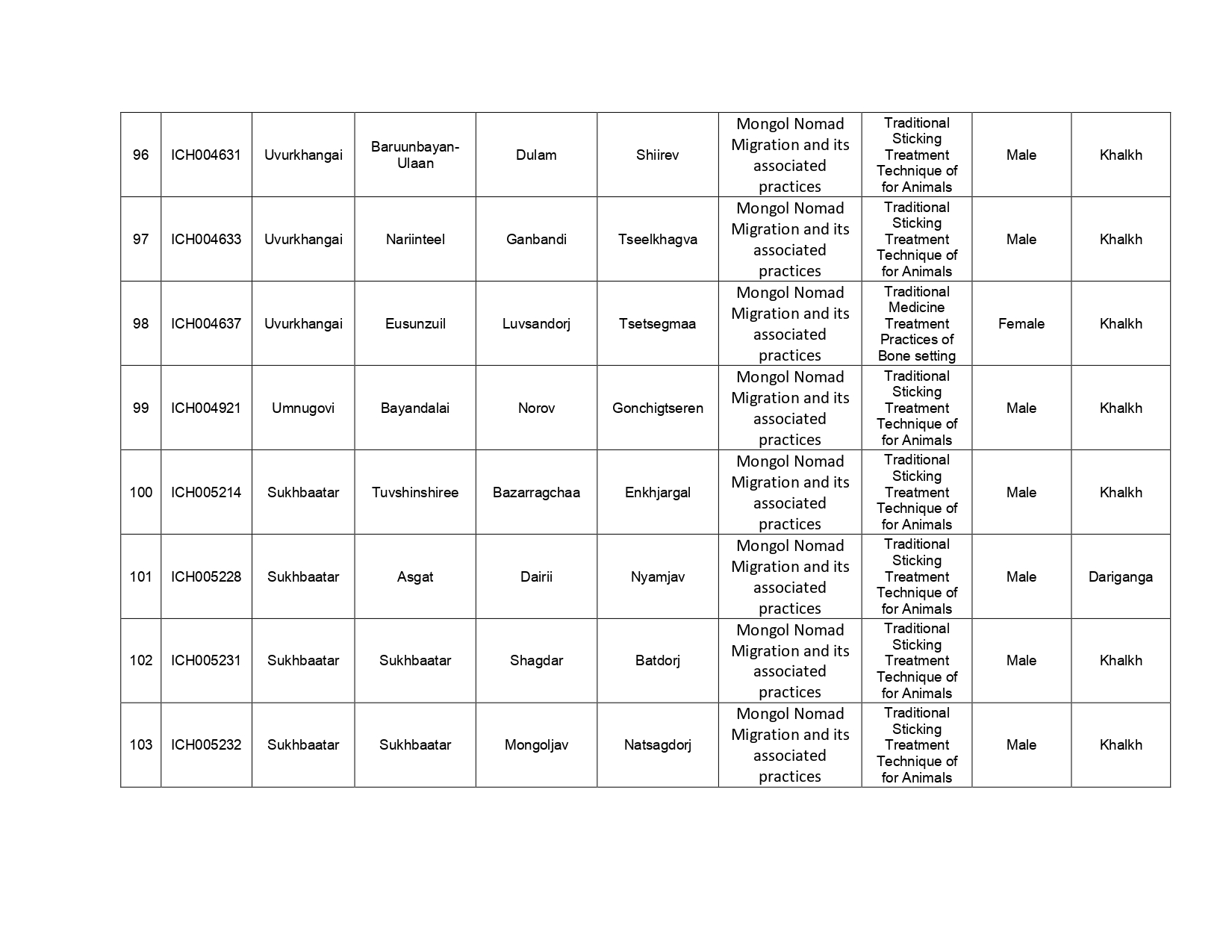

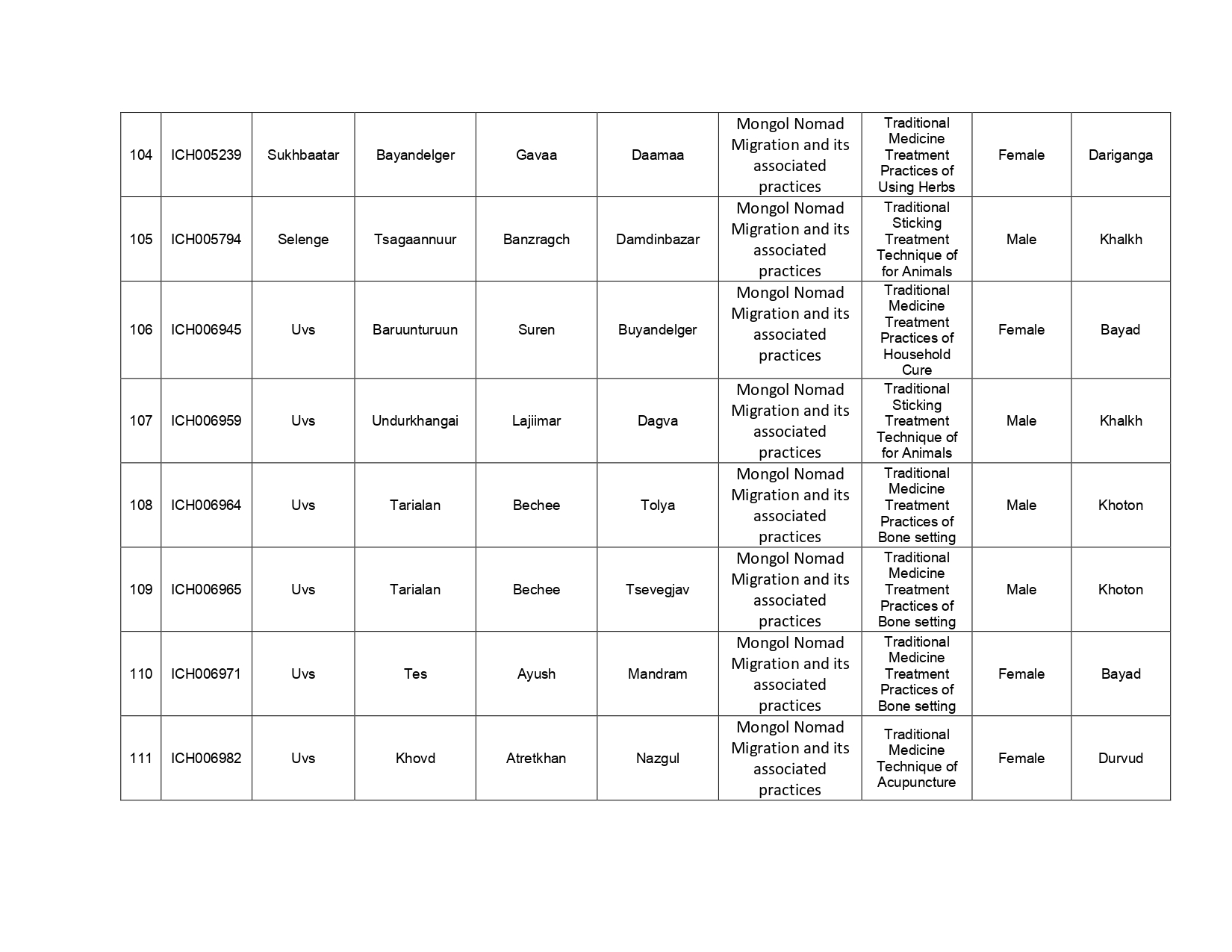

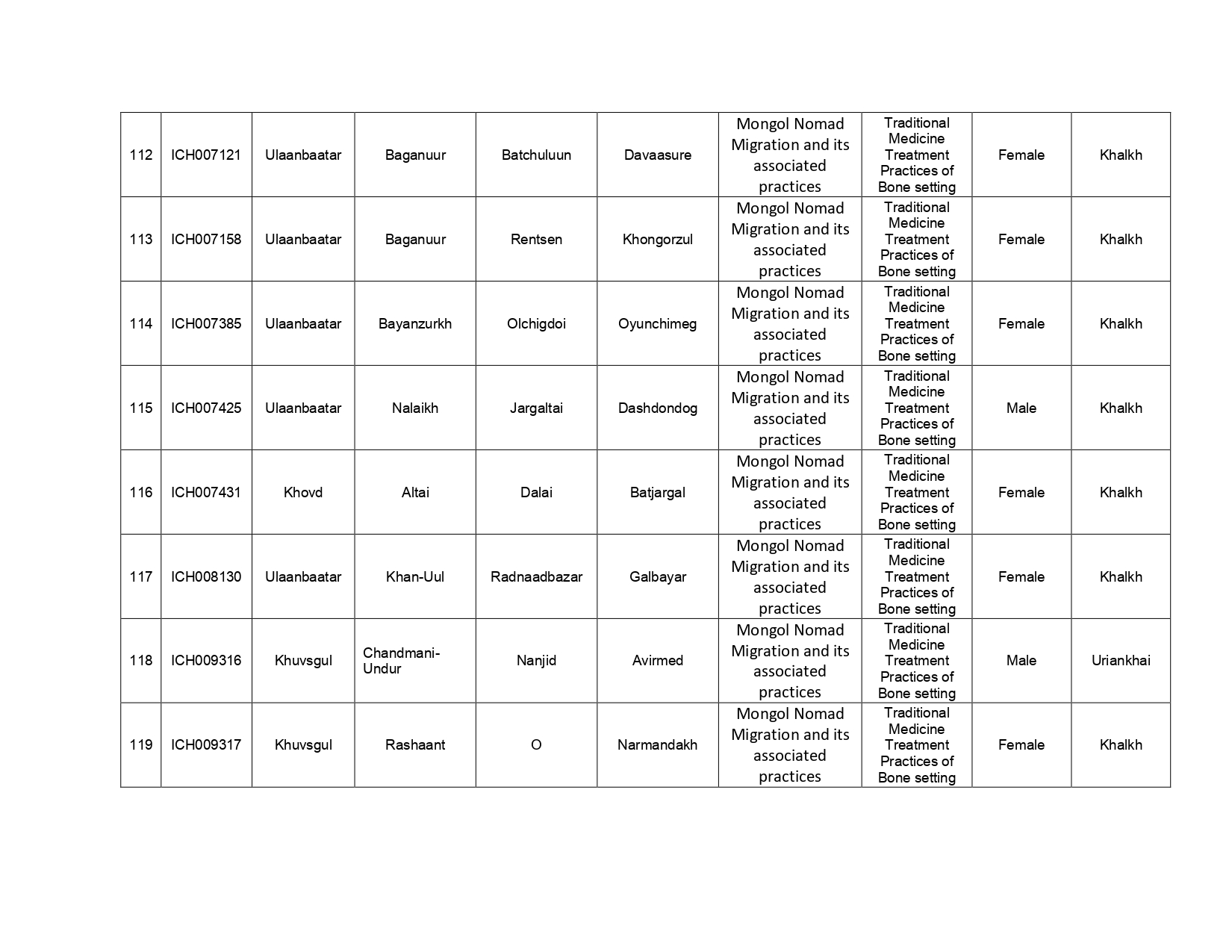

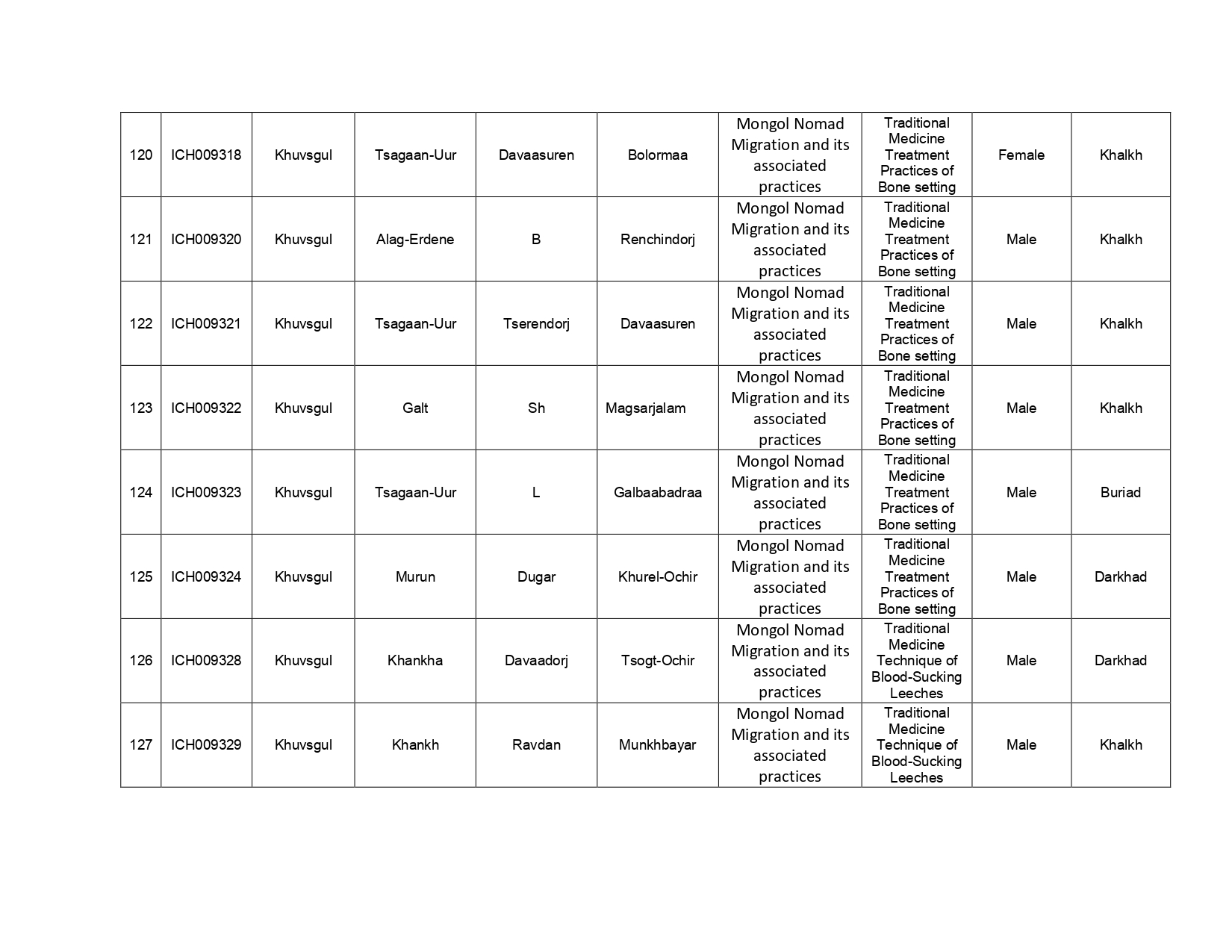

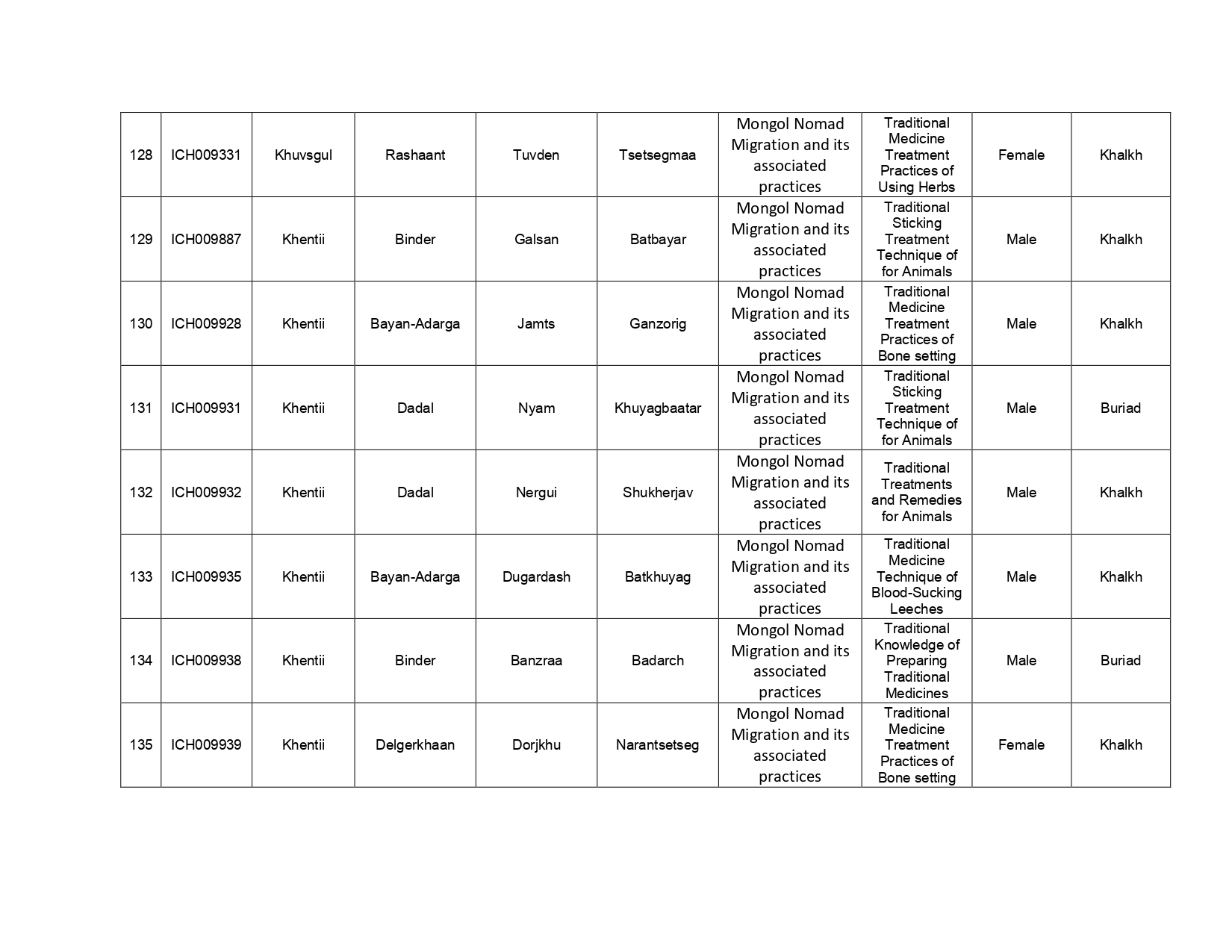

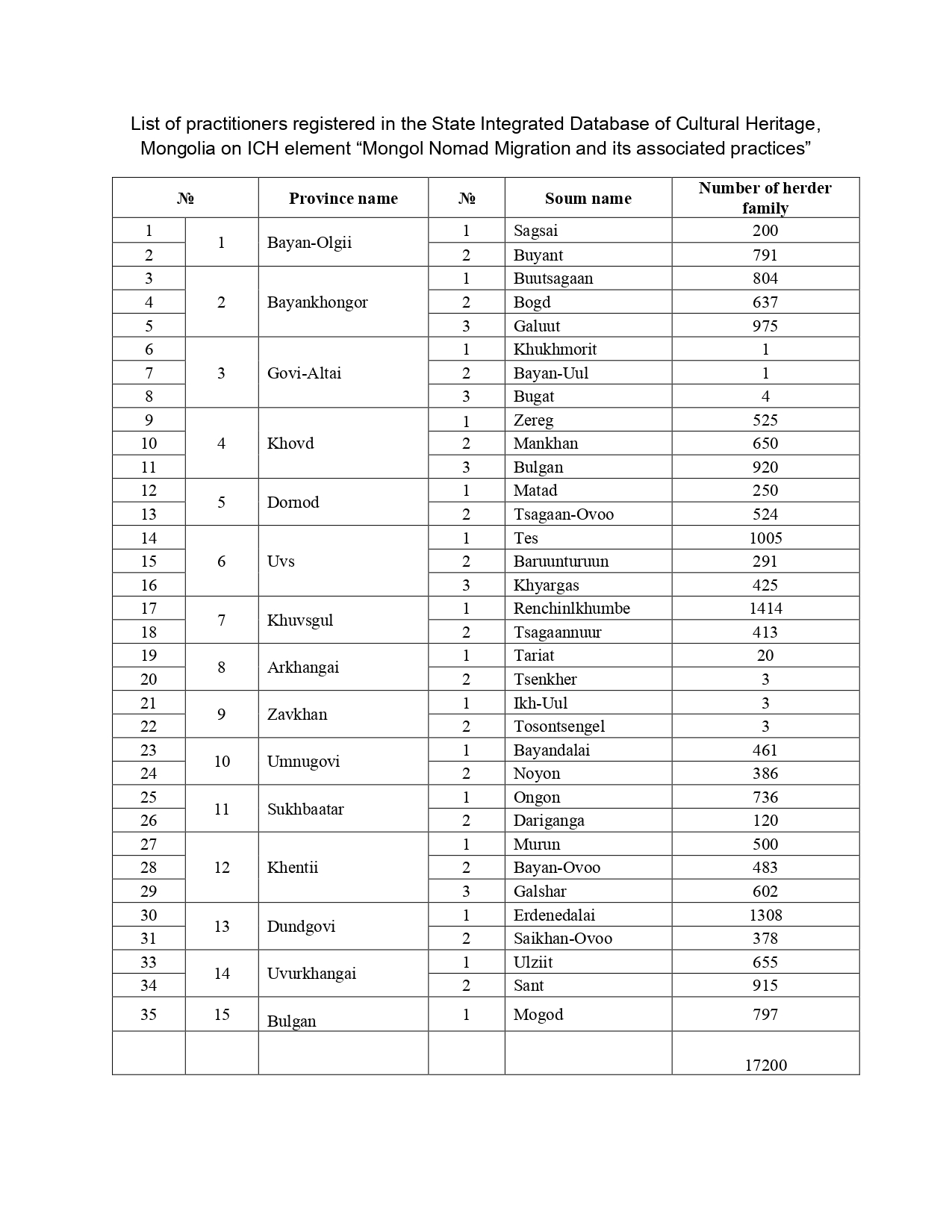

Communities

According to the 2021 National Census of Mongolia, there are approximately 246,200 families who still practice traditional nomadic animal husbandry, all of whom are involved in nomadic migration practices. In addition, the primary registry of intangible cultural heritage for the capital and 21 provinces of Mongolia contains data on 17,200 herders. This registry is formally registered in the National Integrated Database and Register of Cultural Heritage.

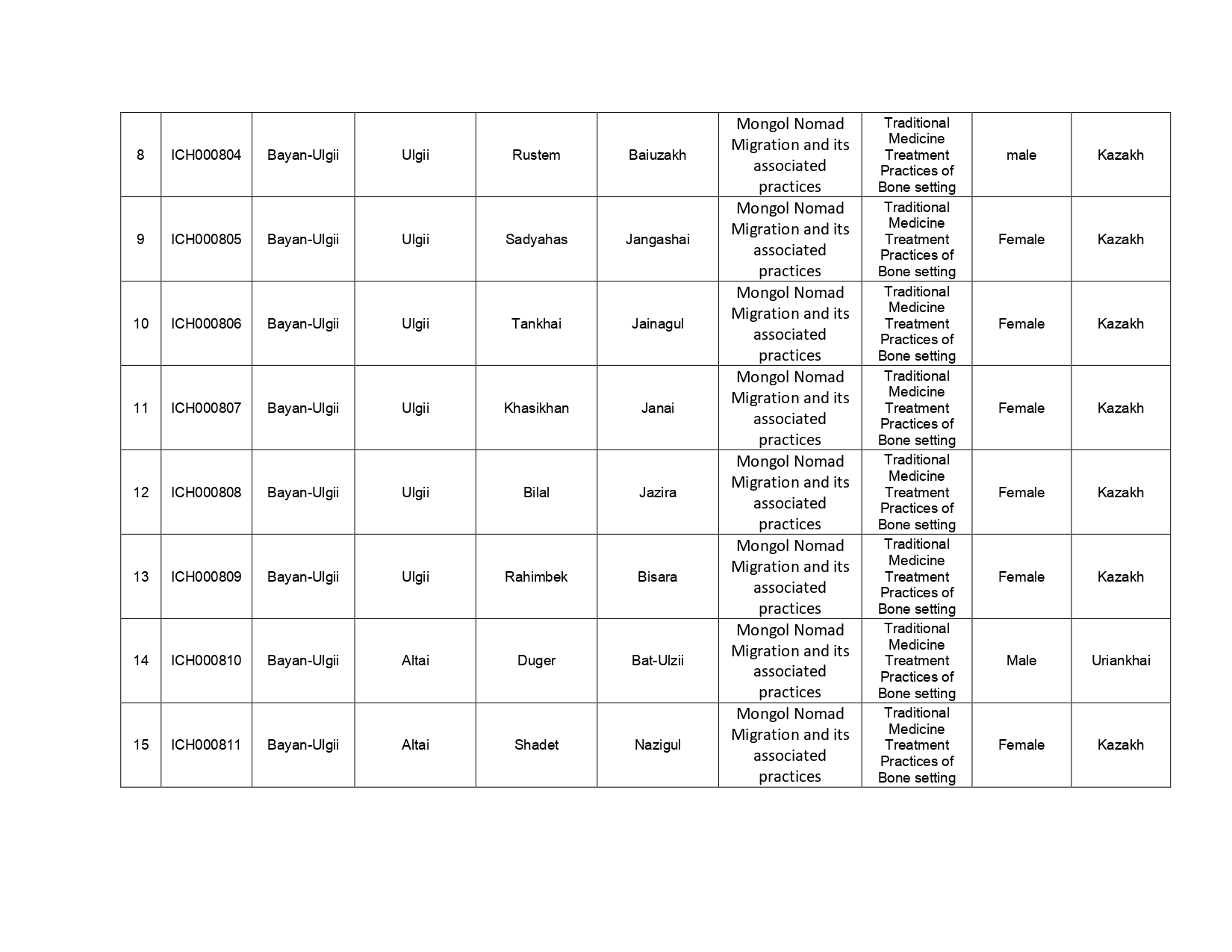

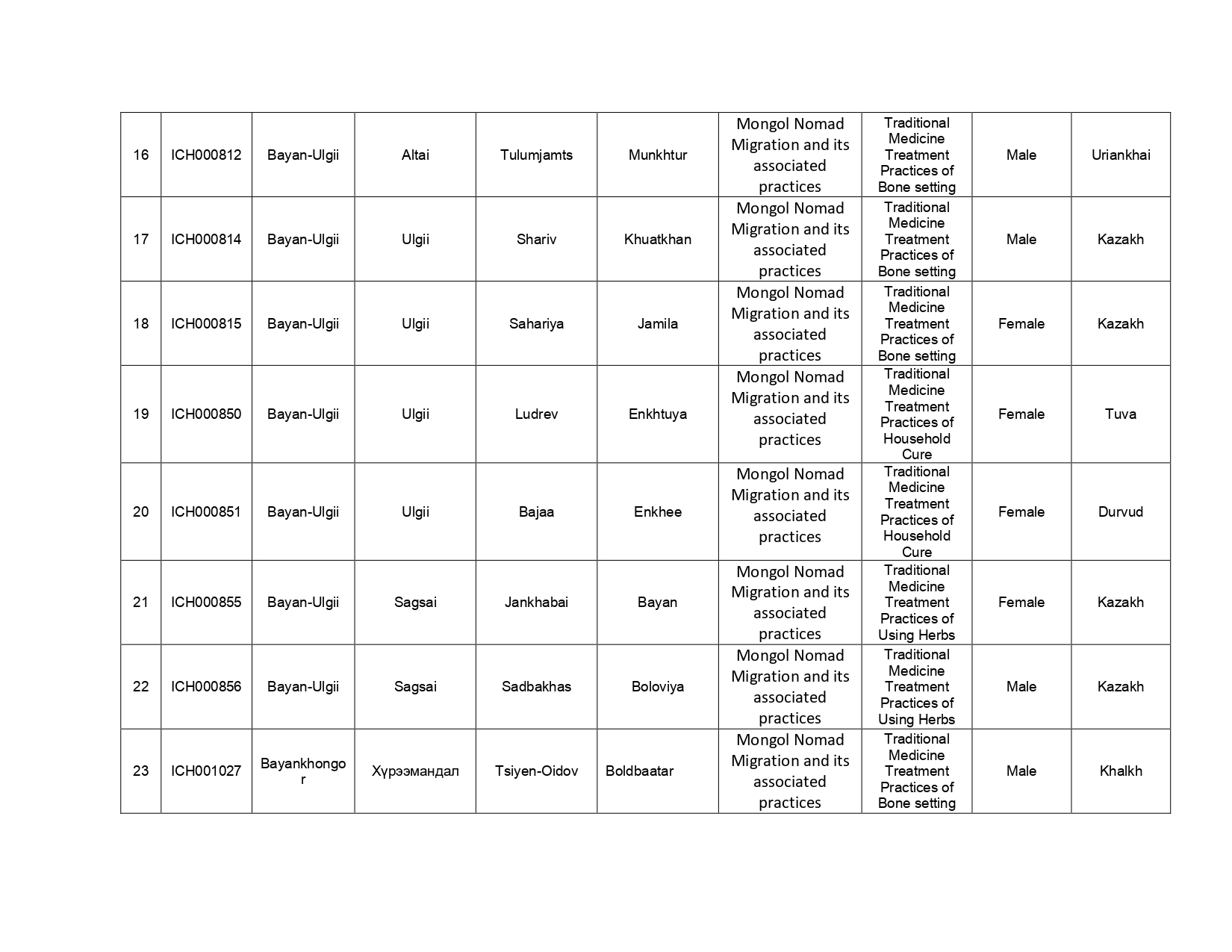

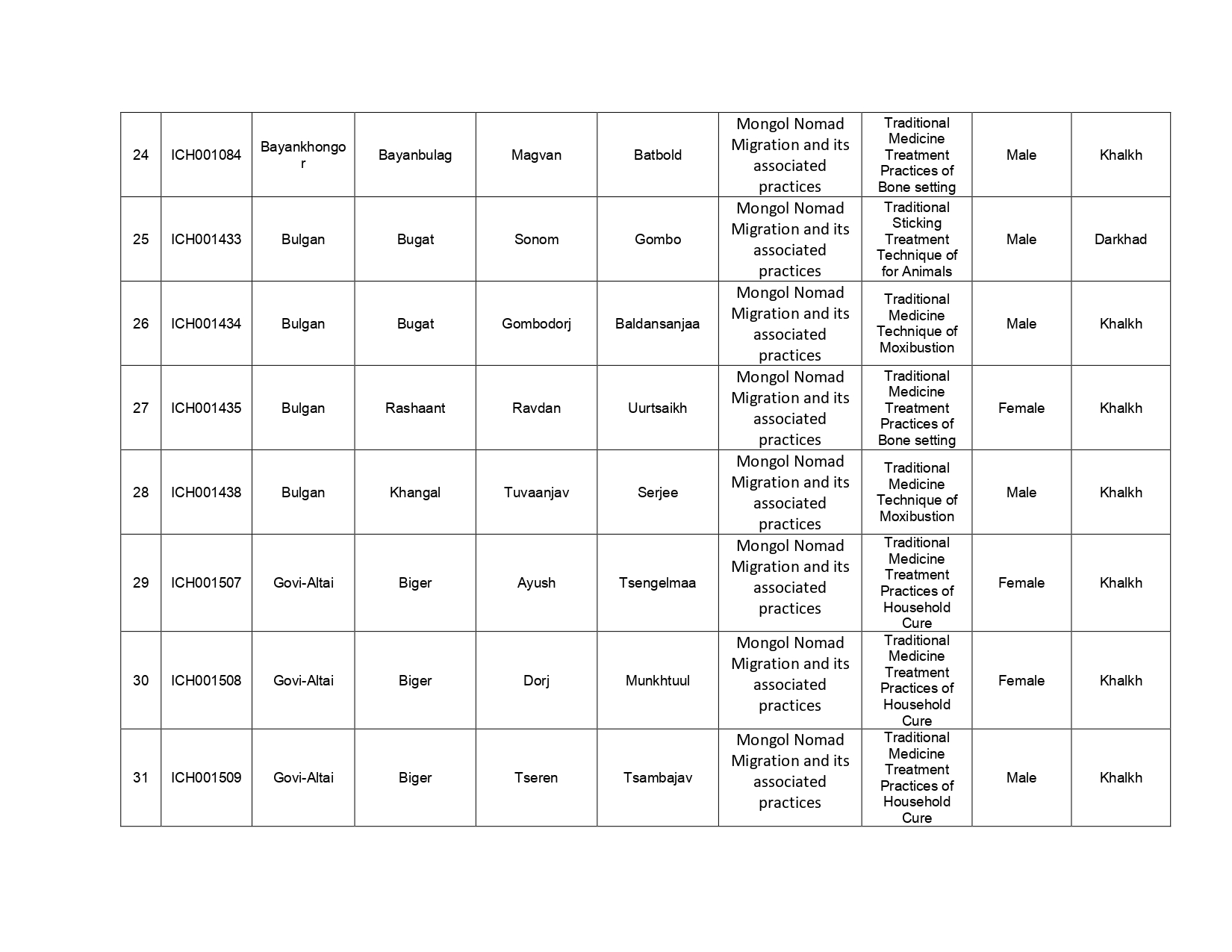

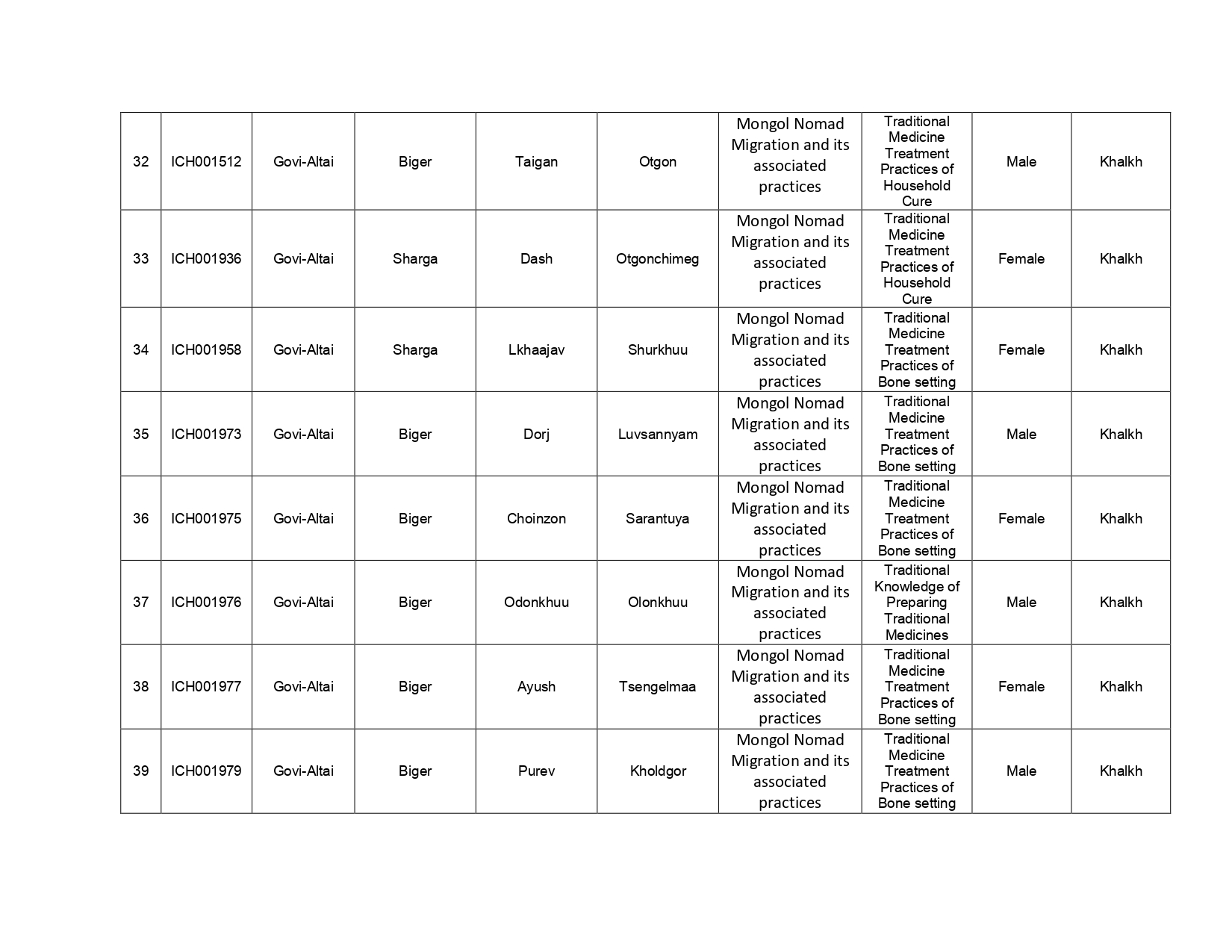

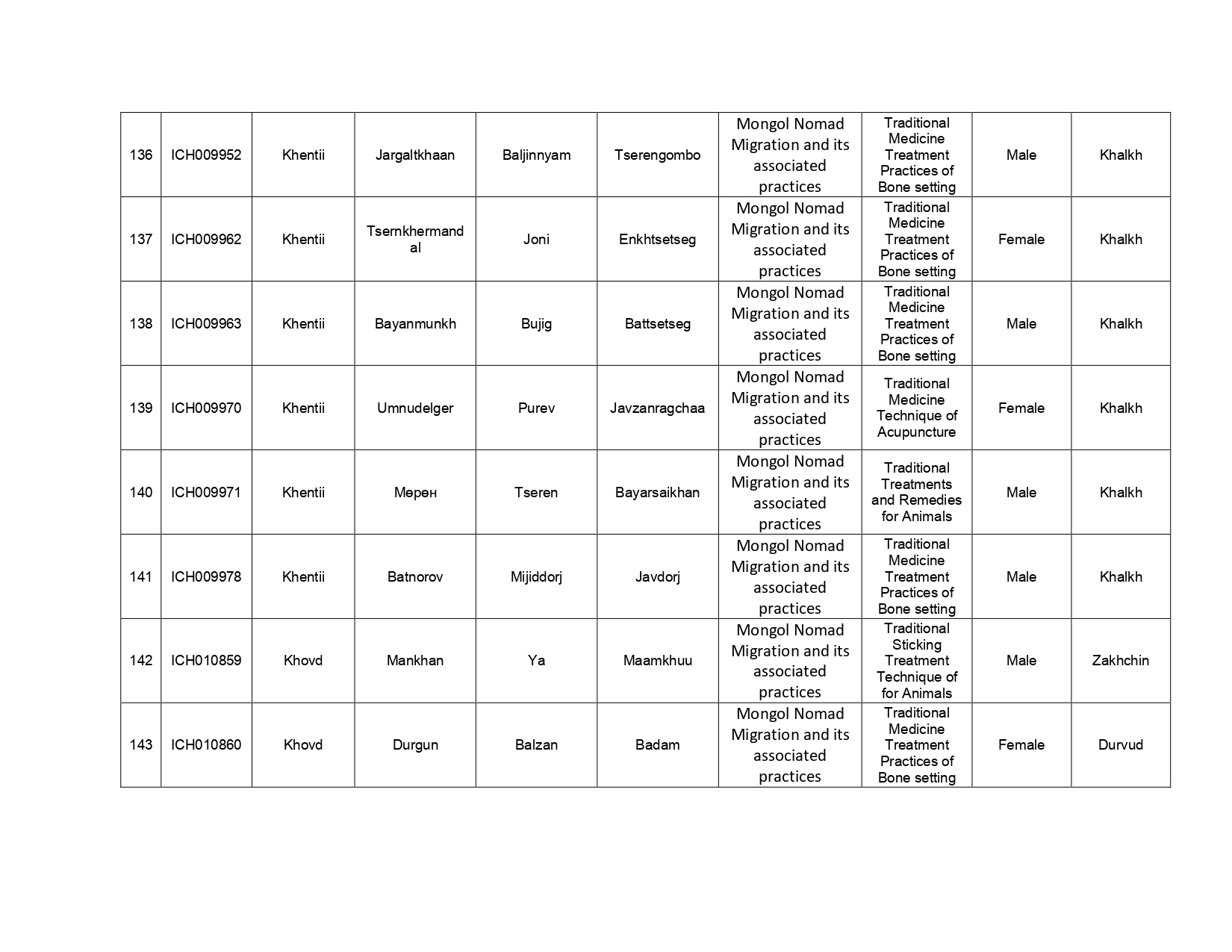

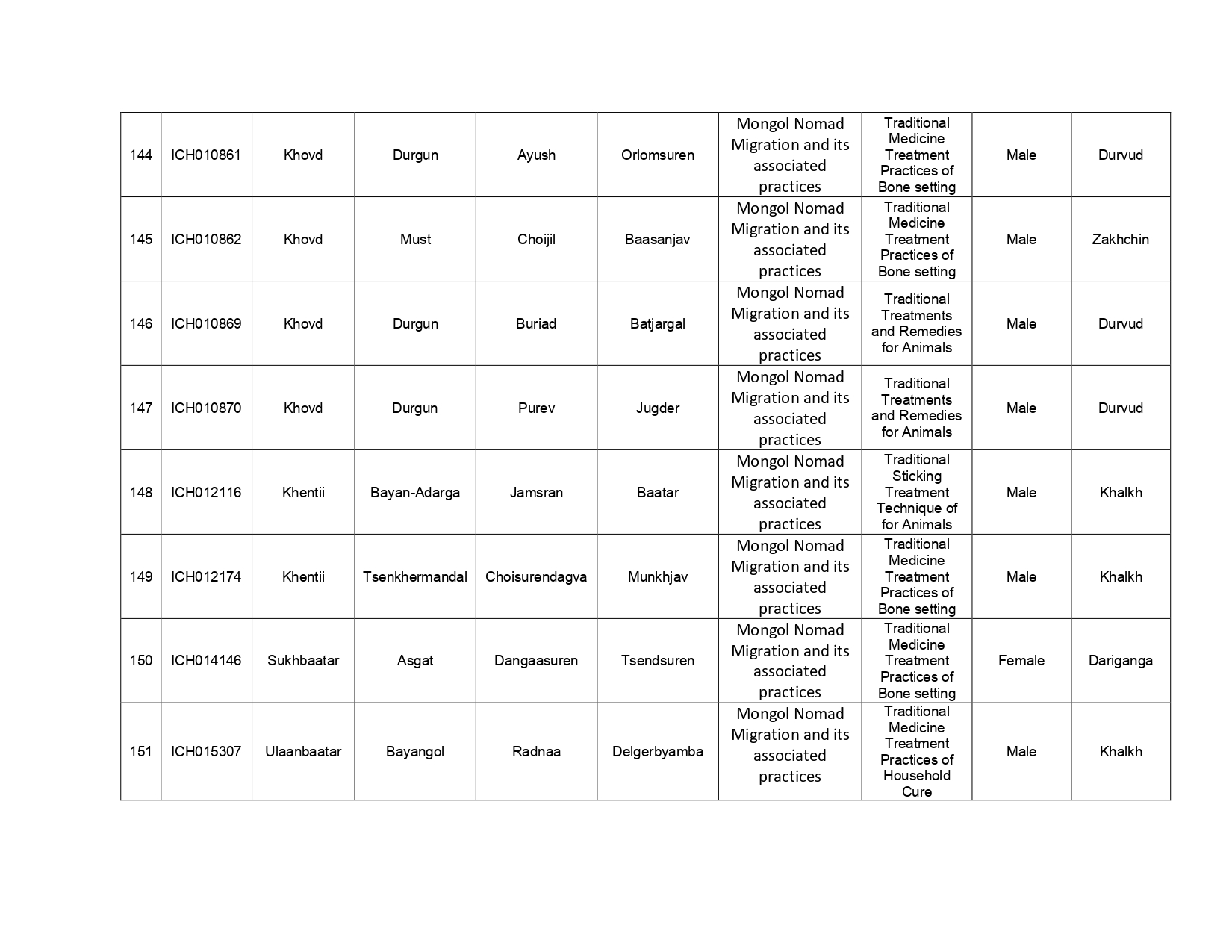

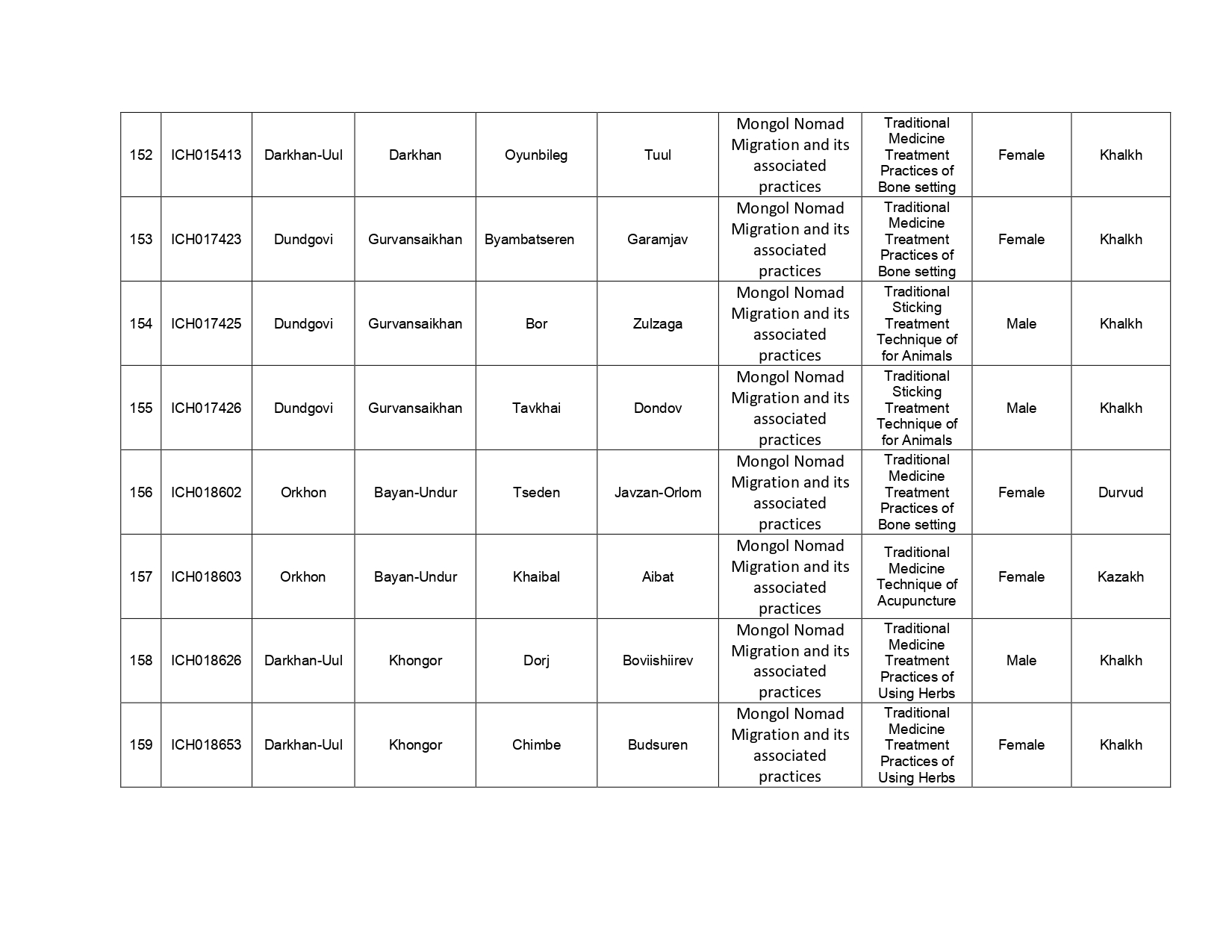

Inventory of Practitioners of Mongol Nomad Migration and its associated practices.pdf

List of practitioners registered in the State Integrated Database of Cultural Heritage.pdf Dissemination of ICH element

Dissemination of ICH element

Currently, there are no migration techniques utilized in high mountain areas, taiga, certain regions of Khangai and Gobi in Altai. Therefore, traditional migration methods for reindeer, camels, and yaks persist. Although machinery has been used for migration since 1990, Mongolian children start learning crucial skills for their nomadic lifestyle from a young age.

This includes taking care of livestock, selecting them, navigating migration routes, and assembling and disassembling gers (yurts). The animals used for migration are selected and trained meticulously from a very young age, which strengthens the bond between them and the people. This tradition ensures safe transportation during migration. Every member of the family plays an important role in these practices, which are passed down from generation to generation.

Linked ICH elements

On November 29th, 2019, the "Mongol nomad migration and its associated practices" were approved to be included in the "Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Mongolia" by the 759th Order of the Minister of Education, Culture, Science, and Sports. It falls under the III domain No6 of "Social practices, festive events, and traditional rituals," and is also linked to No3 "Customs associated with taboos" of the same domain. It is further connected to the IV session "Knowledge and Practices Concerning Nature and the Universe" domain, specifically No1.

"Traditional Knowledge and Practices of Protecting and Preserving Nature," No2. "Traditional Knowledge and Practices of Observing and Studying Nature," No3. "Traditional Knowledge and Practices of Choosing New Pasture," and No4. "Traditional Astronomical Knowledge." It is also included in the VI session "Traditional Knowledge and Techniques Associated with Herding Livestock" domain, which comprises No1. "Traditional Knowledge of Herding Horses," No2.

"Traditional Knowledge of Herding Camels," No3. "Traditional Knowledge of Herding Cattle," No4. "Traditional Knowledge of Herding Sheep," No5. "Traditional Knowledge of Herding Goats," and No6. "Traditional Knowledge of Herding Yaks." Moreover, the "Mongol nomad migration and its associated practices" are also related to the IV session "Traditional Techniques, Knowledge, and Practices Concerning Nature and the Universe" domain, comprising No1.

"Traditional Knowledge of Observing the Sky and Forecasting Weather," No2. "Traditional Knowledge of Observing Plants and Pasture," and No3. "Traditional Knowledge of Observing Animals and Birds." It has also been included in the Urgent Safeguarding List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Mongolia.

Video (Mongol Nomad Migration and its associated practices EN)

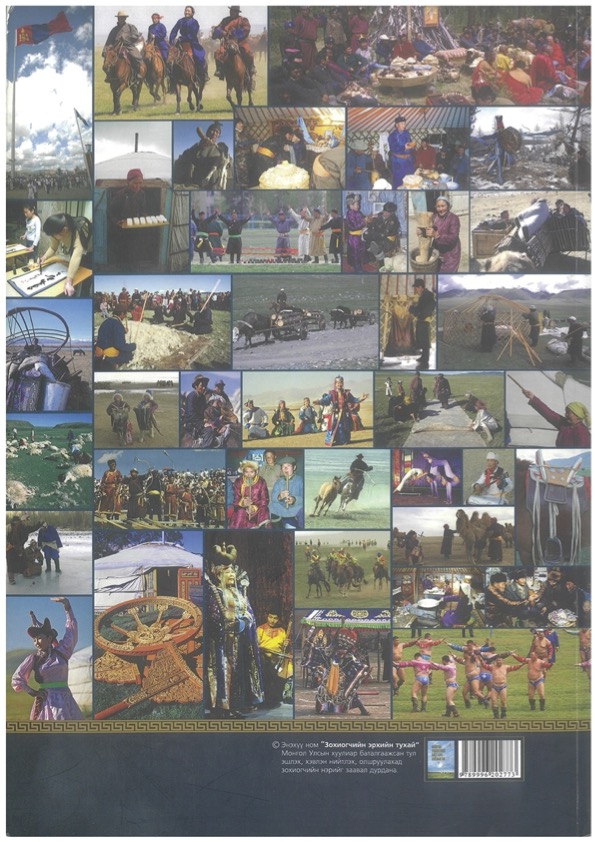

Photos

Additional information: International Year of Rangelands and Pastoralists

Executive summary

More than half of the Earth’s land surface is classified as rangeland, those lands on which the indigenous vegetation is predominantly grasses, forbs or shrubs that are or can be grazed, and which are used as a natural ecosystem for raising grazing livestock and wildlife. The health, productivity and environmental sustainability of these lands are directly critical to the livelihoods and cultures of more than 500 million pastoralists, including agro- pastoralists, rangers, and animal keepers around the world.

Billions more benefits from these systems for tourism, wildlife and biodiversity, meat and milk and other agricultural products, mining, renewable energy and other uses. To increase knowledge and understanding about these ecosystems and the people who rely on them, the Government of Mongolia proposes to establish the observance by the United Nations (UN) of an

International Year of Rangelands and Pastoralists.

Rangelands are faced with increasingly erratic climates, rapidly increasing human populations in some countries and rapidly declining or even abandonment in others, and a fast pace of unsustainable land-use change. But in recent years, an increasing appreciation of the value of pastoralism and transhumance for maintaining healthy rangelands has led to innovative approaches and technologies for sustainability of pastoralism. These landscapes and livelihoods need urgent attention from many sectors (e.g. agriculture, environment, health, education, trade) and many stakeholders (e.g. policymakers, herders, land managers, environmentalists, legislators, businesspeople, scientists, civil society, youth and women).

An International Year of Rangelands and Pastoralists (IYRP) can provide the impetus and momentum necessary for a worldwide understanding of the importance of these lands to global food security and environmental services. It can call attention to the need for sustainable management and restoration, and enlightened policies in both developed and developing countries, enhance the perceived natural and cultural values of rangelands and pastoral livelihood systems, enhance pastoralists’ rights and pride in their own cultural systems and traditions (especially among youth), and foster innovation towards sustainability and overcoming poverty. An IYRP can enhance governments’ awareness and capacities to deliver on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and other global development and environmental goals in such marginal areas.

Suggested action by the Committee

Building on the momentum the UN Decade on Family Farming 2019–2028 and the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration in 2021–2030, and the International Year of Camelids 2024, there is an urgent need to raise awareness on the challenging future facing pastoralists’ livestock production systems and the rangelands they depend on – multi-faceted challenges that are different and very severe among such remote and mobile populations, including access to health and education services, access to economic inputs and markets, land-tenure security, conflict resolution, and investment in rangeland ecosystem improvement.

The Committee is invited to:

a. Review the proposal made by the Government of Mongolia in partnership with Ethiopia, Argentina, Australia, Iran and Spain to establish the observance of an International Year of Rangelands and Pastoralists, and provide guidance as deemed appropriate;

b. Review and amend the draft Conference Resolution as presented in Appendix A.

I. Background

A. Defining rangelands and pastoralists

More than half of the Earth’s land surface is classified as rangeland¹, those lands on which the indigenous vegetation is predominantly grasses, grass-like plants, forbs or shrubs that are grazed or have the potential to be grazed, and which are used as a natural ecosystem for raising grazing livestock and wildlife. Rangelands may include native grasslands, savannas, shrublands, pasturelands, woodlands, wetlands, deserts, steppes, pampa, llanos, cerrado, campos, veld, tundra, alpine communities and marshes².

The health and productivity of these lands are directly critical to the livelihoods and cultures of more than 500 million pastoralists around the world, many of whom are indigenous peoples. Pastoralists are people who raise livestock or semi-domesticated animals on rangelands, including ranchers, nomads and transhumant herders³.

B. Rangelands and pastoralists are custodians of sustainable development

Pastoral agriculture is a way of life for many communities in worldwide and over time it has evolved and supported environmental protection of rangeland landscapes and herders’ livelihoods. For example, in Mongolia as of 2017, one-third of the national labor force was employed in pastoral agriculture and the sector comprised 8.4 percent of the country’s exports and 24 percent of its GDP. Within the agriculture sector, almost 83 percent of total production comes from the traditional pastoral livestock sector, which includes 66.5 million herds, with average of 390 herds per herder’s family and totally occupying 72 percent of the country’s territory. Nomadic livestock husbandry has developed in its long history in harmony with nature and the environment to adapt to the harsh climatic conditions of rangelands. Healthy rangelands provide important benefits to humans, such as food security, medicine, local and regional economies, tourism, and they are critical for supporting ecosystem services, such as nutrient cycling, oxygen production, wildlife habitat, biological diversity and soil formation. For Mongolians and many other nations pastoralism is their culture, tradition and historical heritage, which was transferred from generation to generation. Currently more than 300 herders, where representing all provinces of Mongolia, supporting for the International Year of Rangelands and Pastoralists by signing to the proposal (Annex A).

Regulatory ecosystem services of rangelands include water purification, protection of soil from sand and water erosion, and flood protection. Recent evidence points to the higher productivity of rangelands under sustainable pastoralism than other land uses. Pastoralism is increasingly recognized as one of the most sustainable production systems on the planet and plays a major role in safeguarding ecosystems and biodiversity in natural grasslands and rangelands⁴.

C. Conversion of rangelands and pastoralism

Conversion of native grasslands to produce soy and other crops, and feed for livestock, is among the greatest threats to these ecosystems. Unhealthy and unproductive rangelands, native grasslands and pasturelands/grasslands destabilize countries, endanger national security, compromise economic productivity and rob our youngest generation of opportunities for a prosperous future. Often their conversation may result in short term gains, but long-term environment disasters such as the 1930’s Dust Bowl of the American and Canadian prairies and Yellow dust storms forming in Asia, due to desertification and land degradation. Many forces threaten the productivity and ecological integrity of these lands and their caretakers. Common threats in both developed and developing countries include: restrictions on moving or rotating animals, programs to settle pastoralists, unsustainable grazing practices, expansion of arable cropping into areas best suited as rangeland, breakdown of common property systems, land fragmentation, generational succession and rural exodus⁵, damaging fire, invasive plants, and harmful subsidies and policies.

Land degradation and desertification are intensifying in many parts of the world on account of climate change, overgrazing, infertile cultivated land and mining activities, among other causes. For example, in Mongolia as of 2015, land degradation and desertification have become a concern for 76.8% of the total territory, including 22.9% of which is severely affected. The land for mining has expanded because the areas with mining licenses were increased. According to the measurements throughout the territory of Mongolia for the period 1940–2016 without any interruptions or gaps, the average annual air temperature has increased by 2.2°С and warming has much intensified, in particular, since 1988. According to the assessment of climate change on the country’s environment and socio-economic sectors, pastoral animal husbandry and farming are highly impacted⁶

D. Access to development

Having been impacted by “benign neglect” ⁷ in many developing countries for many generations, pastoralists are among the poorest and most marginalized. Rural services barely reach them. Mobile pastoralists such as nomads and transhumant herders face discrimination and conflict.

Products derived from rangelands such as meat and milk face intense competition from unsustainable intensive livestock systems. Essential ecosystems are destroyed when rainforests are converted to feed production. The unregulated use of growth hormones and pesticides, and unbalanced subsidies in commercial systems, can lead to unfair competition for pastoralists.

Many examples of sustainable pastoralist practices exist⁸. Such systems are critical to achieving food and water security as well as resilient local and national economies, and to improving environmental conditions such as carbon sequestration, biodiversity and protection of land and ecosystems.

E. Crisis proportions

However, rangelands and pastoralists are facing drying and increasingly erratic climates, rapidly increasing human populations, fast pace of unsustainable land-use changes and threats to ecosystems, and increasing conflicts associated with increasingly armed banditry, terrorism, drought and access to diminishing natural resources.

There are also growing public health concerns about over-consuming animal-source foods and the impact of livestock on the environment and growing economic inequalities and uncertainties. At the same time, these inequalities and uncertainties particularly of poor and marginalized pastoralists, and increasing conflicts associated with drought and access to diminishing natural resources. Therefore, these landscapes and livelihoods need urgent attention from many UN sectors (e.g. agriculture, environment, health, education, trade) and many stakeholders (e.g. policymakers, herders, land managers, environmentalists, legislators, businesspeople, scientists, civil society, youth and women).

¹ “A case of benign neglect: Knowledge gaps about sustainability in pastoralism and rangelands“, UN Environment, CRID, 2018

² The International Terminology for Grazing Lands and Grazing Animals, 2011. (http://globalrangelands.org )

³ (IUCN/UNEP 2014 - http://cmsdata.iucn.org/downloads/wisp_green_economy_book.pdf).

⁴“A case of benign neglect: Knowledge gaps about sustainability in pastoralism and rangelands“, UN Environment, CRID, 2018

⁵ In many developed countries, but also increasingly in developing countries, the younger generation is unable or unwilling to take over their family operations.

⁶ State of Environment of Mongolia 2015–2016, MNET, Ulaanbaatar

⁷ “A case of benign neglect: Knowledge gaps about sustainability in pastoralism and rangelands“, UN Environment, CRID, 2018

⁸ See for example: http://globalrangelands.org; http://rangelandsinitiative.org

Pastoralists are explicitly recognized in the 2030 Agenda as a group of peoples who should benefit from achievement of the SDGs. Amongst all 17 SDGs, there is a cluster of SDGs critical in achieving sustainability of rangelands and pastoralism. Ensuring that all people have access to safe, nutri- tious and sufficient food all year (SDG 2) is the core goal, which depends on success in significantly reducing rural poverty (SDG 1) and increasing attention to the special needs of pastoral women, elderly and rural youth (SDG 5), while also ensuring inclusive education for all citizens, particularly, herders in remote rural areas with a limited access to information and learning opportunities (SDG 4). Empowering pastoralist women could be achieved through increasing their participation and leadership in decision-making over livestock production and incomes of rural communities (SDG 5).

Healthy and productive rangelands throughout the world are needed to realize the goals of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, especially the targets for sustainable agriculture, water management, sustainable energy and economic growth, combating and adapting to climate change, and promoting sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems.

B. Relevance to UN and other partners

Despite their neglect, pastoralists and rangelands are receiving increasing attention from a number of UN agencies. FAO has the mandate to support the development of all food-related systems including pastoralism, and in recent years has increased its investment in this. The FAO Voluntary Guidelines of Good Governance and Tenure Technical Guide on “Improving governance of pastoral lands⁹” highlight the importance of land tenure security and the strengthening of pastoralist institutions. FAO’s Pastoralist Knowledge Hub advocates for sustainable pastoralism, pastoralist-friendly policies and a strong pastoralist civil society. This initiative supports the proposal for an IYRP through its events and communication channels.

The United Nations Environment Assembly (UNEA) recognized the importance of sustainable pastoralism and responsible consumption of livestock during its second meeting in May 2016. In that meeting, 158 countries passed a resolution (UNEA L.24) on “Combating desertification, land degradation and drought and promoting sustainable pastoralism and rangelands”, calling among other things for raising global awareness.¹⁰

As implementation process for this agenda, in the fourth meeting of UNEA in March 2019, Member States passed Resolution UNEP/EA .4/L.17 on: “Innovations on sustainable rangelands and pastoralism” submitted by the African Group of countries5. This resolution urges that Member States to strengthen global efforts to conserve and sustainably use rangelands in particular in the context of the UN General Assembly Resolution (A/RES/73/284) on the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration in 2021–2030, acknowledging ongoing global efforts to introduce a proposal for an IYRP to the FAO’s Committee on Agriculture.

The UNEA-4 resolution also welcomes the global and regional initiatives and efforts aimed at preventing and reversing the loss of biological diversity and ecosystem functions and services and taking note of the substantive body of work on rangelands and pastoralism under UN organizations such as the Food and Agricultural Organization and the UN Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD).

The UNCCD urges “development and implementation of national and regional policies, programs and measures to prevent, control and reverse land degradation and mitigate the effects of drought through scientific and technological excellence, raising public awareness..., thereby contributing to poverty reduction.” Improved pastoral systems can reverse the destructive effects of drought and create economic opportunity for rural populations.

As recommended by UNEP gap analysis report need to implement regional and global integrated data assessment on pastoralists and rangelands in order to support future strategies and actions for ecosystem sustainability and the green development at different levels.

In December 2016 during a side event at the Convention on Biological Diversity COP 13 in Cancun, 28 government and 48 civil society organizations signed a strong statement that recognizes the value of rangelands, grasslands and pastoralism for conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity. Some Governments have also declared their support for strengthening pastoral societies in the context of security and development (e.g. the N'Djamena Declaration of May 2013), and enhancing resilience (e.g. the Nouakchott Declaration of October 2013).

The International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) supports governments, pastoralists and mixed farming communities in negotiating and strengthening local solutions for rangeland governance including agreements securing pastoralists’ migratory routes, improving access to and management of water points, animal health services, and creating additional income opportunities, in particular for women, through new pastoralist products and markets. Its hosting of the International Land Coalition (ILC) including the ILC Rangelands Initiative is testimony to its commitment to securing lands for rural populations including pastoralists.

The International Land Coalition ( ILC) supports pastoralist networks of Civil Society Organizations ,CSO’s , in all regions of the world on sustainable rangelands management with securing tenure rights of rangelands for local communities , including poor, women and indigenous people. ILC also promoting inclusive decision making on rangeland use, effective actions against land grabbing and sustainable locally managed rangeland ecosystems.

In December 2016 during a side event at the Convention on Biological Diversity COP 13 in Cancun, 28 government and 48 civil society organizations signed a strong statement that recognizes the value of rangelands, grasslands and pastoralism for conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity.

Many other national and international organizations are promoting similar positive actions and have joined together in establishing an International Support Group for the IYRP, showing their commitment to this event, including: International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA), International Land Coalition (ILC), International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), Conservation International, International Rangeland Congress, International Grassland Congress, Society for Range Management (USA and Australia), IPICYT (Mexico),networks such as CELEP (Coalition of European Lobbies for Eastern African Pastoralism) and many international and national NGOs and CSOs.

An IYRP will increase a worldwide understanding of the importance of these lands to global food security and environmental services, and call attention to the need for sustainable management and enlightened policies in both developed and developing countries.

It can enhance the perceived natural and cultural values of rangelands and pastoral livelihood systems, enhance pastoralists’ rights and pride in their own cultural systems and traditions (especially among youth) and foster innovation towards sustainability and overcoming poverty. It can boost efforts for investment in restoration and rehabilitation of degraded rangelands, native grasslands and pasturelands.

Furthermore, an IYRP can enhance governments’ awareness of and capacities to deliver on the SDGs and other global development and environmental goals in rangelands. It can allow low- forest-cover countries to demonstrate their commitments to the UN climate change agreements and to more accurately quantify their nationally determined contributions, all of which can enhance their ability to access multilateral funding such as through the Global Climate Fund, Global Environment Facility, World Bank, IFAD etc.

It can encourage those countries with a large area under rangelands to exchange experiences, share best practices, and perhaps form a network or caucus to continue to enhance awareness on rangelands and pastoralists well beyond the designated year.

B. Growing recognition

The IYRP initiative builds on a recognition that development actions in rangelands need to be sustainable and benefit pastoralists equitably. A growing global pastoralist movement has emerged over the past decade and has made a number of calls for increased international recognition for their culture and land-use system.

Pastoralist organizations, communities and herders in many countries are requesting and supporting to declare IYRP. Global gatherings of pastoralist have issued declarations for such recognition, for example in Segovia, Spain (2007), Gujarat, India (2010), in Kenya (2013), in Rome, Italy (2016) and at the 8th Multi Stakeholder Partnership Meeting of Global Agenda for Sustainable Livestock in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia (2018). Therefore they will take center stage in all activities for sustainable rangelands and pastoralism under the IYRP objective. During the proposal development period more than 20 international, regional and national organizations worldwide supporting the Mongolian proposal for the declaration by UN the International Year of Rangelands and Pastoralists (Annex B).

The heightened profile resulting from an IYRP will help pastoralist associations and networks to have a more visible profile and platform to press for their rights to development, to establish National Days on rangelands and pastoralists, improve legal recognition of rangelands and pastoralists, exchange best practices and solutions to problems, and revive/reinforce cultural traditions and diversity.

C. National and international actions

A work plan will be developed that will consist of both national and international actions. Each month of the International Year could highlight a special theme, such as: the importance of rangelands, grasslands and pastoralists; improving legal and policy base on land-tenure security; social and economic services for pastoralists; climate change and resilience; biodiversity and ecosystem services; soils, water and land use; sustainable consumption and production of livestock; indigenous and local knowledge and innovation; women and youth; sustainable technologies.

Examples of activities that could be undertaken by countries and partners are:

(1) National-level events, including showcasing successful sustainable pastoral systems, awards and prizes, technology fairs, video documentaries, a National Day of Pastoralists and Rangelands and World Herder Day, educational material, etc.;

(2) An international conference on SDGs and their impact on pastoralists and rangelands, bringing together environmental, social and economic aspects in an integrated vision;

(3) Launching of actions aimed at implementing the recommendations of the UN Environment Gap Analysis on knowledge and information about rangelands and pastoralists and the UNEA-4 Resolution L.17;

(4) International social media campaigns and video productions to raise awareness of producers, consumers and policymakers worldwide;

(5) Pastoralist gatherings sponsored by several initiatives and networks, such as FAO Pastoralist Knowledge Hub to share local knowledge and strategize practical solutions.

IV. Appendix A

A. Draft FAO Conference Resolution

Recognizing that healthy grassland and rangeland ecosystems are vital for contributing to economic growth, resilient livelihoods and the sustainable development of pastoralism; regulating the flow of water; maintaining soil stability and biodiversity; and supporting carbon sequestration, tourism, and other ecosystem goods and services, as well as distinct lifestyles and cultures,

Aware that a significant proportion of the earth's terrestrial surface is classified as rangeland and grassland, that these biomes dominate land cover in dryland countries and countries affected by desertification, that a significant number of pastoralists in the world inhabit rangelands and grasslands, and that pastoralism is globally practiced in many different forms,

Recognizing that pastoralism is a dynamic and transformative system linked to the diverse cultures, identities, traditional knowledge, historical experience of coexisting with nature, and distinct way of life of indigenous peoples and local communities across the globe,

Also recognizing that rangelands and pastoralists, having contributed to enhancing and maintaining biodiversity, food security and sustainable management of rangelands, face urgent and different challenges around the world, including: widespread land degradation, loss of biodiversity, increasing vulnerability to climate change; lack of strong policy and legal base and land tenure insecurity; insufficient investment; inequitable development; inadequate levels of literacy; lack of adequate and relevant technology, infrastructure and access to markets; unsustainable changes in the use of land and natural resources; forced migration from and

abandonment of rangelands; limited access to social and extension services; and faced with insecurity of both the pastoralists and the communities through which they traverse,

Acknowledging that efforts aimed at achieving sustainable rangelands and pastoralism need to be rapidly up-scaled so as to make significant impact in achieving all Sustainable Development Goals in drylands, mountains, Arctic circle, and other areas used by pastoralists; and that an International Year of Rangelands and Pastoralism in 2026 would help to provide the necessary attention and investment required for achieving such urgent change by 2030,

Noting that urgent and appropriate legal protection is needed of collective and individual land and natural resources, in order to manage grazing areas, wildlife, water sources livestock movement, risk and resilience, and to enable land-use planning and ecosystem management by pastoralists and relevant public entities,

Also noting that well-developed and fair production value chains that can help provide equitable economic opportunities and end extreme poverty among many pastoralists, will require the development of appropriate market infrastructure, information and communication channels; value-addition and niche businesses built on sustainable and healthy livestock products; appropriate health and trade regulations; certification systems and payments for environmental services; and an enabling environment providing for multiple use of land (livestock, conservation, tourism, mining, renewable energy, etc.),

Recognizing the significant contributions being made by the scientific community, non- governmental organizations, indigenous peoples organizations, pastoralist associations, and other relevant civil society actors; including innovative approaches towards achieving sustainability,

Further recognizing the relevance of sustainable rangelands and pastoralism to several subprograms and thematic areas of the United Nations, including the Food and Agricultural Organizations, the United Nations Environment Programme, the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification, and International Fund for Agricultural Development, and acknowledging their collaborative efforts with intergovernmental and civil-society partners,

- Decides to declare 2026 the International Year of Rangelands and Pastoralists so as to raise global awareness of these resources.

- Invites the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, the United Nations Environment Programme, and the International Fund for Agricultural Development, mindful of provisions contained in the annex to Economic and Social Council resolution 1980/67, and the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification and Drought, to assist in facilitating the implementation of the Year in collaboration with Governments, relevant organizations, non-governmental organizations, civil society, and all other relevant stakeholders;

- Invites the scientific community and civil society to actively participate in implementation of the Year in collaboration with the United Nations and governments, in particular through new and innovative research, knowledge generation, monitoring and assessments, to be disseminated through relevant global congresses, assemblies, social media and business community;

- Invites the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and the United Nations Environment Assembly to keep the General Assembly informed of progress in this regard, bearing in mind paragraphs 23 to 27 of the annex to Economic and Social Council resolution 1980/67, on activities resulting from the implementation of the present resolution, which elaborates on, inter alia, the evaluation of the Year;

- Stresses that the costs of all activities that may arise from the implementation of the present resolution above and beyond activities currently within the mandate of the lead agencies should be met through voluntary contributions, including from civil society and the private sector;

- Requests the Director General to submit this Resolution to the Secretary General of the United Nations;

- Recommends the present Resolution to the General Assembly for adoption.